You are about to become obsolete.

When labor becomes scarce, expensive, and/or unreliable, business owners start looking for alternatives. For most of the past 30 years, a very attractive alternative was offshoring—to countries like China, where labor was cheap, plentiful, and reliable. In the past three years, the COVID pandemic and the maturing of once-cheap labor markets, plus the increasing obviousness of China’s IP theft and overall hegemonic ambitions, have begun to reverse that trend. Economists are now forecasting “the end of globalization,” with labor scarcity continuing for decades as the workforce shrinks. Big companies, desperate for workers, are even indicating a willingness to hire people without college degrees for positions that traditionally required them.

To me, though, the idea that labor will continue to be scarce seems wrong. As I see it, mechanization and AI are now moving onto the steepest part of the innovation slope, and will soon start “disemploying” people all the way up the labor value chain, from manual trades to those overpaid millennial marketing girls sipping lattes on TikTok. Even I, with my fairly challenging profession and decades of experience, am likely to be left jobless at least a few years before I’d like to retire.

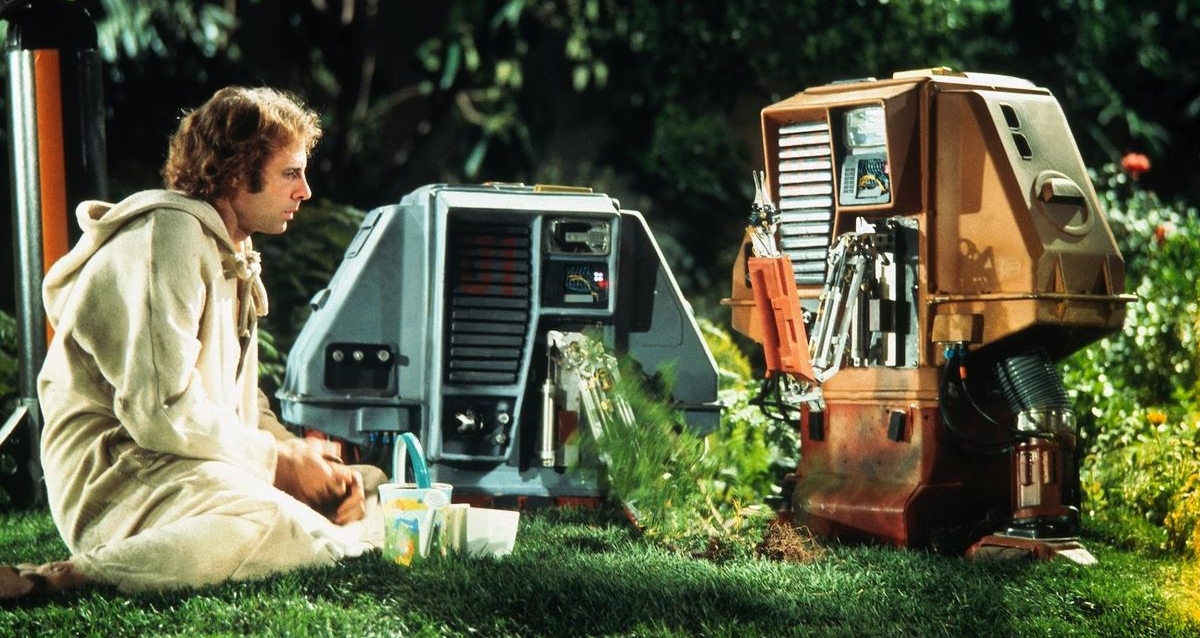

AI has taken longer than expected to arrive in useful forms, but is now definitely arriving and ready to start disrupting. It can, technically if not yet legally, drive cars, tractors, trains, and boats; fly planes and drones; and guard warehouses. The mechanization technology underlying humanoid robots has been making big advances too—such robots now can open doors, climb stairs, recover from falls, hold and manipulate heavy objects, etc. Once such robots are mass-produced and made available for leasing, their use as replacements for factory workers, waiters, construction workers, checkout clerks, etc. will become a viable proposition. Will we have to wait as long as five years before that starts?

AI language-processing software that can be taught, or can teach itself via the Internet, should start displacing office worker bees well before then—and by worker bees I mean basically anyone whose job consists largely of emailing, writing reports, filling out spreadsheets, and doing other routine kinds of paperwork. And we’ve all seen the AI text-to-image and text-to-movie packages that were unleashed recently and have been improving at a rapid pace. How long will it be before a single writer, working with one of those algos, generates a feature-length film on his own? A year from now? Two?

Essentially, we’re facing the prospect of the abrupt end of the labor market, an institution that has been at the center of human civilization for millennia.

I’m aware that critics of earlier forms of labor-saving technology, such as the Luddites and their ilk, were somewhat shortsighted in their predictions of mass labor displacement. These early industrial workers were themselves displaced in large numbers, and in that sense had every reason to complain. What they failed to see was that the labor-saving innovations that displaced them would, on the whole, lead to greater productivity and economic growth, and ultimately a net rise in demand for labor.

But that was then, and this is now. The tech that’s going to be released into the world in this decade will be capable of displacing humans from their jobs much faster than the latter will be able to keep up. In other words, if you are laid off because your employer or clients can just buy an AI package to do the same job more cheaply, and you then decide to retrain for some “AI-proof” job, it’s quite likely that that “AI-proof” job will be overtaken by AI long before you can get into it. Even if that job stays available, you’d be competing for it with an exponentially rising number of other displaced human workers.

It’s impossible to predict in detail how this will all play out. But I can easily imagine an early phase in which language-processing AI, vehicle AI, warehouse robots, and a few other related innovations are hailed as game-changers for businesses and other organizations, allowing them to do much more with fewer workers and at less cost—and alleviating inflationary labor shortages along the way. Close on the heels of that “denial” phase, though, will come the bargaining, depression, and acceptance phases, as the pace of disemployment accelerates. I see this as an ouroboros—snake-eating-its-tail—process, because it involves the economy effectively consuming itself, i.e., destroying, with every increment of growth and investment in innovation, the employment earnings that are the principal fuel for a modern economy.

There may be no stable equilibrium in this process for a long while. Governments probably will try to tax businesses, especially AI-using businesses, to fund welfare payments to the unemployed masses, but will that work? Even if governments could manage it fiscally, what would be the psychological effect on tens of millions of people who can no longer earn a living for themselves? (We already know that men become easily depressed when unemployed.)

It also seems unlikely that Western governments would ever simply disallow the use of AI and robotics. One of the great lessons of the mass immigration era is that Western governments, ostensibly “democratic,” like having electorates made up of financially stressed people whose votes can be bought with government largesse.

It stands to reason that the disemployment situation will be easier in countries that currently have relatively small workforces—or rely on guest workers who can be sent quickly back to their home countries if needed. By the same logic, countries with open borders and huge, low-skill, permanent immigrant populations, like the US, could be in serious trouble. Those countries will suddenly have many millions of excess mouths to feed, and to do so might easily require taxation levels that trigger capital flight.

I’m not totally averse to the idea that at the end of this transition lies a society in which robots do everything for near-zero cost and humans can stay busy however they like without worrying much about money. But it’s hard to believe this transition will occur without historic levels of pain. I’ve written often in this space about various drivers of Western decline, collapse, and general upheaval; the now-imminent “ouroboros economy” of AI and robotics is surely another one.

***