Forget #TheFutureIsFemale—women have already remodeled the Western world

Feminists these days spend a lot of time worrying about male-dominated culture—“patriarchal culture,” “sexual harassment culture,” “rape culture,” “the culture of silence,” and so on. But shouldn’t they be acknowledging the influence that women now have on culture: on workplace culture, on media culture, on campus culture, on American culture, and on Western culture generally? That feminizing influence may be the greatest single driver of the rapid social changes seen in recent decades.

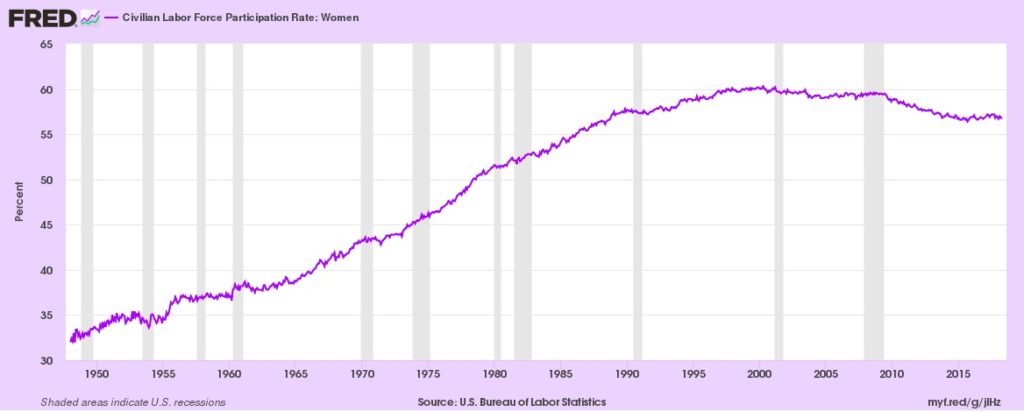

Consider the following U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics chart of women’s civilian labor force participation rate.

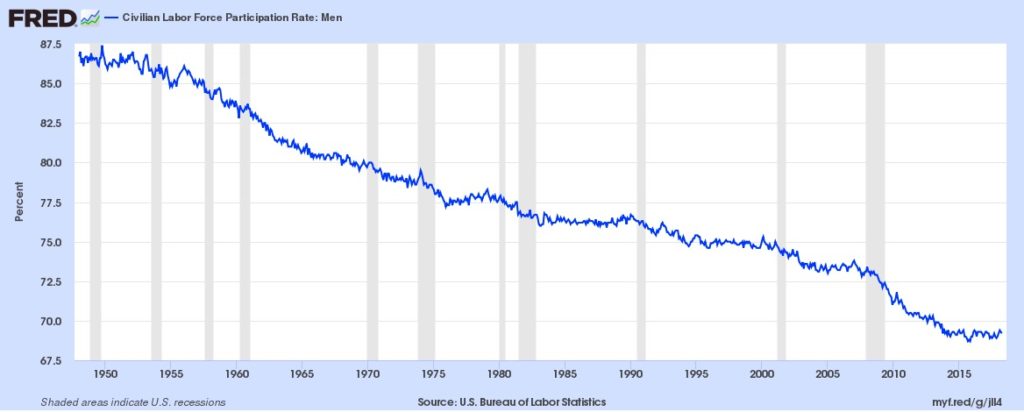

It shows that in 1950 only about 30 percent of working-age women were in the workforce, but by 2000 that figure had jumped to 60 percent and rivaled the participation rate for men, which had been in decline since the early 1950s. In other words, by 2000 the U.S. workforce had been mostly gender-integrated. On average, workplaces by then had almost as many women as men.

The historic significance of this migration on its own appears to have been underappreciated. Women never made such a move, to such a degree, in any large human society in the past. It significantly altered the structure of ordinary life.

But women in the late 20th century didn’t just move into the workforce. They moved into its upper ranks, to professions that strongly influence societal culture and policy. They became journalists, public relations specialists, lawyers, academics, novelists, publishers, filmmakers, TV producers, and politicians, all to an unprecedented extent. In some of these culture-making professions, by the 1990s and early 2000s, they had achieved parity or even dominance (e.g., writers, authors, and public relations specialists) with respect to men. Even where they fell short of full parity, they appeared to acquire considerable “veto” power over content. A 2017 report by the Women’s Media Center noted evidence that at the vast majority of media companies, at least one woman is among the top three editors.

Why is the greater presence of women in culture-making professions important? Because women, on average, think differently than men on a wide range of subjects. That psychological differentness is well established from experiments, and is reflected in the well-known “gender gap” in voting and policy choices—a gap that is even larger when considering women who are maritally independent of men, i.e., single women, one of the fastest-growing demographics in the country.

If one accepts that culture is a strong determinant of behavior, which it is really by definition, it follows that putting a high proportion of women into senior roles in culture-making professions, basically for the first time ever, will have changed the culture and therefore changed how people on average tend to think and act. It won’t have changed everyone absolutely; we are not blank slates. But it will have moved the collective needle—shifted the so-called Overton Window of publicly acceptable opinion, and shifted average behavior as well, even average male behavior. That is, in fact, the underlying logic of organizations like the Women’s Media Center, which have explicitly sought to alter, to feminize, the content of mass media and the resulting attitudes of the public by putting more women into newsrooms.

How would culture and policy have changed as a result of women’s new influence? Presumably in ways that reflect feminine psychological traits.

For example, women appear on average to be more empathetic and compassionate, more emotionally sensitive. Some of the most striking social changes of the last few decades appear to have been driven by a cultural shift in that direction:

- More generous welfare programs

- Expansion of the concept of welfare to include more types of intervention (affirmative action, etc.) and more groups needing intervention

- Expansion of the definitions of “harm,” “offense,” and “trauma” (“microaggressions,” “triggers”)

- Increased attention to psychological trauma in law and medicine, leading to a greater acceptance, and thus a higher prevalence, of trauma-related syndromes such as PTSD (and the recovered-trauma-memory syndromes of the 1990s)

- Less tolerance of deaths in war; but, ironically, a greater inclination to enter foreign conflicts in response to emotion-evoking atrocities portrayed on television

- Less tolerance for capital punishment

- Less restrictive immigration policy

- More emphasis in media and policy contexts on emotion-evoking stories of individuals (e.g., pitiable refugee children) rather than dry analyses of long-term outcomes

- Suppression of any kind of emotionally disturbing speech (“hate speech,” “mansplaining,” etc.) and even fields of scientific inquiry that are likely to evoke negative emotions;

- Less affinity for traditional, constitutionally protected forms of confrontation in the legal and political spheres, i.e., less support for open debate, free-speech rights, and “due process of law.”

- Suppression/replacement of words that evoke emotional discomfort (e.g., “abortion clinic” becomes “women’s health center”)

That’s just from one set of closely related traits. Certainly there are others. For example, women for obvious evolutionary reasons appear to have an instinctive fear of dietary and environmental toxins, which can become pronounced during pregnancy (“morning sickness,” nesting reflex, food aversions). Is it just coincidence that women’s cultural ascendancy in Western countries corresponds to a huge rise in diet-, drug-, and environment-related concerns encompassing the Green movement, anti-GMO attitudes, “detox” fads, the “herbal medicine” racket, “organic foods” preferences, and even the anti-vaccine movement?

Then there is the issue of systematizing. Experiments by psychologists and everyday observations by parents, etc. suggest that whereas the average “male” brain is adapted for understanding and building systems, the average “female” brain is . . . not so much adapted for that. A cultural shift away from traditional “male,” systematizing thinking across society could again explain many specific social changes. One is the great, still-ongoing migration from traditional religions with their managerial hierarchies and highly systematized theologies to new, more loosely structured and personalized spiritual groups, such as Evangelical Christian groups, New Age movements, and neo-pagan groups (e.g., Wicca) which give prominent roles to women. Another plausible reflection of this de-systematizing tendency is the long-term decline of interest in engineering among U.S.-born students, who are now outnumbered by foreign students at U.S. engineering grad schools.

One of the most obvious sex-related differences in human behavior concerns aggression and violence. Women on average are far less violent than men, and consequently make up only about 7 percent of the U.S. prison population. If women have had an unprecedented feminizing effect on the “public mind” in recent decades, in principle that would have reduced the propensity for aggression and violence even among men. Indeed there has been a striking downward trend in violent crime rates in the U.S. in recent decades—a trend that would be even stronger if all the violent crimes committed by people born and raised in traditional, patriarchal societies, e.g., Mexico, were excluded.

How could men have been feminized to this extent? By having less testosterone, for example. The ways in which sex hormones rise and fall in response to social cues is an under-studied area, but two trends stand out alarmingly: Age-adjusted testosterone levels in men have been falling in Western countries in recent decades, and—as one would expect from that—sperm counts have been falling too. Interestingly, those sperm-count studies suggest that whatever is causing the trend in Western societies has been having less effect, or no effect at all, in traditional, i.e., patriarchal societies.

Why is it “alarming” that male testosterone levels and sperm counts have been dropping in Western countries, if one result is less violent crime? Because that’s not the only result. Declining testosterone also means declining fertility and probably also a declining motivation to marry and raise a family. Here again the statistics are consistent with the idea of a Great Feminization. The U.S. in recent decades has seen not only a decline in the marriage rate, but also a collapse of the birth rate for U.S.-born women, to levels below what demographers consider necessary to maintain the population. The “U.S. population” now grows chiefly because of open-door immigration and births to immigrant mothers.

Am I crazy to link female emancipation and near-equality in the workforce to all these bad results, including population collapse? Well, no—I’m only putting forward a hypothesis, and one that seems well grounded in the data. Obviously many factors contributed to the social changes that have swept across the West in the past half century or so. But that women were one of those factors seems undeniable. And the possibility that they were, and continue to be, the dominant factor seems worth discussing, not least because of the potential implications for the future. Yet . . . there has been no discussion. I’ve been circulating this idea for years now, in one forum and another, and it gets no traction at all. It isn’t shot down by some fact or logical disproof; it’s just ignored or dismissed without reason. No “respectable” publication will touch it. I can’t help wondering if that response is yet another reflection of women’s new cultural power.

published 6 Mar 2019

**

Postscript (3/25/19): Apparently a similar theory, blaming the West’s fertility decline on feminism, has been kicking around in “far-right” circles. That probably helps explain why doors have tended to shut in my face whenever I’ve tried (over the past 7+ years) to get a version of this essay published–and I’ve been reduced to publishing pseudonymously in fringe publications or on d-i-y websites. In case it’s not already clear, my “great feminization” idea is mainly about cultural feminization, doesn’t have anything directly to do with the formal “feminist” movement, and doesn’t require any dire prediction about population decline/replacement. Also, though it should be irrelevant, I’m not some woman-hating incel; I’m happily married, etc. My interest in the topic of sex differences in culture and policy attitudes developed from the fact that I, a male, work in a profession that is increasingly female-dominated.

Author’s note (Oct 2022):

I’d appreciate it, reader, if you would link to my essays on cultural feminization (or otherwise cite them) wherever you see this topic being discussed. I’ve been writing about “cult-fem” for more than a decade—which, as far as I know, is much longer than anyone else. Some of my essays have circulated widely in recent years, and I’ve even placed one in a moderately well-read webzine. I like to think that my contributions have helped seed what is becoming an important public discourse. Yet those contributions of mine are almost never acknowledged by the better-known opinionators who have ventured into this realm in the last year or so. Being pseudonymous and writing principally from a personal website seem to have left me in the unhappy state of being “much read but seldom cited.” (I discuss the general problem of citation in the Internet age in my short essay “The Tree of Knowledge.”)

Also, though I don’t charge a subscription to this website, or put ads on it, or even solicit donations, you could buy a copy of my e-book (see image below, linked to its Amazon page) if you’d like to support my writing.