Terminal demoralization, the Fermi Paradox, and the true “end of history”

“What is it, then, that this craving and this helplessness proclaim to us, but that there was once in man a true happiness of which there now remain to him only the mark and empty trace, which he in vain tries to fill from all his surroundings, seeking from things absent the help he does not obtain in things present? But these are all inadequate, because the infinite abyss can only be filled by an infinite and immutable object, that is to say, only by God Himself. He only is our true good, and since we have forsaken him, it is a strange thing that there is nothing in nature which has not been serviceable in taking His place; the stars, the heavens, earth, the elements, plants, cabbages, leeks, animals, insects, calves, serpents, fever, pestilence, war, famine, vices, adultery, incest. And since man has lost the true good, everything can appear equally good to him, even his own destruction…” —Blaise Pascal, Pensées VII (425)

For as long as I can remember, people have been asking: what comes next after Christianity? The assumption has been that Christianity is dying, and, as Christianity once replaced the polytheisms of the classical era, so should something new and improved come along and take its place.

In the 1980s and 90s, there was a relatively relaxed discussion about the possibility of a kind of globalistic spiritualism (or spiritual globalism) as a successor to Christianity: a blend of New Age-y, Earth Mother paganism and save-the-whales activism. But for all the allure that body of belief and practice had for some, women especially, it seems to have failed so far to cohere into anything institutionally serious. Certainly there have been potent religion-substitutes, most recently political-correctness/wokeism and the high fever of the Great Awokening, but these have been just substitutes, more about policy preferences and coping with socioeconomic inequalities—what we render unto Caesar, as Christ might have said—than any reach for the infinite.

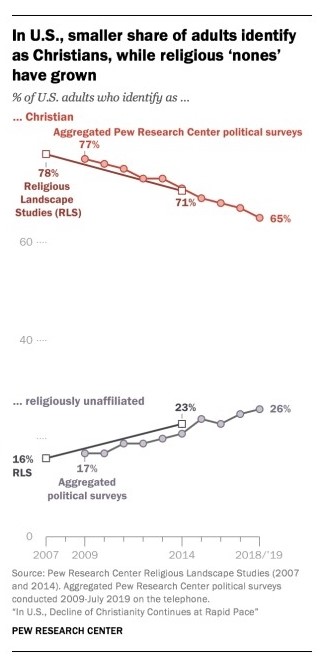

I suppose many Christians would say that their religion isn’t going to be replaced anytime soon, because it has been renewing itself with more popular views and practices, for example prioritizing personal religious experience over traditional ritual and hierarchy—and moreover has been spreading, or at least holding steady, in Africa and Latin America. The problem with this view is that overall measures of belief and religious participation have continued to decline in Western countries, especially in the European home of Christianity but even in the relatively Christian United States.

This clear downtrend among Christianity’s original adherents suggests pretty strongly that this religion in its various forms cannot long survive prosperity, education, and the march of science, and in another few generations will be as defunct, globally, as Zoroastrianism—Islam, Judaism and Buddhism soon following it into the graveyard of theisms.

So again, what comes next? What can fill the proverbial God-shaped hole?

There should be some urgency to the question these days, for it is at least plausible that the decline of Christianity represents the loss of a critical source of vitality for Western societies—and is thus a key factor in their ongoing dissolution. This dissolution is seen in the West’s high rates of mental illness, suicide, drug overdoses, and changing demographics due to immigration; and in falling rates of marriage, household formation, and fertility among those of Western heritage. Indeed, the West now appears to face the usual fate of defeated, devitalized and demoralized peoples throughout history, namely population collapse.

Science as Spiritual Antagonist

Having lived since childhood with the cultural expectation that a religious successor to Christianity is coming, and now in middle age failing to see any sign of such a successor on the cultural horizon, I have to suspect that there won’t be one. Science appears to have been eroding not just one or two particular ideas of God but really any idea of a transcendent being worthy of being worshipped.

From personal experience I expect that this process almost always works only in one direction. A person is baptized and raised in the traditions of one of the big religions, but then in the course of modern education and maturation acquires an alternative, agnostic or even atheistic view of the universe—and when that happens, the person finds it very hard to go back again to embrace religiosity and transcendence. How does one put the toothpaste back in the tube?

Science, in other words, seems to be a potent and broad-acting antagonist with respect to whatever part of the human psyche craves religious transcendence. It embraces the infinite, the cosmos, enough to fill the God-shaped hole, blocking all competitors, but it cannot provide the nourishment, the meaning, the seeds of morality, that one gets from a traditional religion.

Part of the appeal of religion is that it flatters believers with the idea that there is a transcendent Being who considers them important enough to care about. “For God so loved the world” etc. Science obliterates this conceit along with all the other traditional assumptions humans have made about their elevated rank in the universe. “Since Copernicus,” Nietzsche famously wrote, “man seems to have got himself on an inclined plane—now he is slipping faster and faster away from the center into—what? into nothingness? into a ‘penetrating sense of his nothingness?’”

The point here, or the suggested hypothesis, is that science, despite being beneficial to humanity in many ways, is also harmful in a critical psychological way. This is not a new idea, but it and its implications seem to have been underexplored, to say the least. Do science’s malign effects outweigh its benign effects? What if science inevitably sets up a “despair trap” through which any sentient species can pass only with difficulty? Does this putative barrier explain the so-called Fermi Paradox, named for the Nobel-winning physicist Enrico Fermi—who wondered why, if life evolves so easily in the universe, ET civilizations aren’t abundantly evident to us?

Increasingly Toxic Knowledge

Most people are protected from the toxic effects of science by their lack of awareness of, and interest in, the parts of science that deal with the nature of reality and the universe—the parts that blot out the warm sun of the old religions. But, as science takes an ever-larger role in education, in politics, in popular media content and so on, people increasingly will have to confront these toxic parts. Those who absorb such knowledge would not even have to be consciously aware of its toxic effect on them. The pathways and processes connecting learned information to depression and demoralization could work slowly, and entirely “below the limen,” in the unconscious parts of the mind.

In any case, one can easily get the gist of this demoralizing knowledge by skimming through any contemporary popular treatment of cosmology. There one will find laid out, in the weirdly upbeat prose preferred by publishers, cosmologists’ conviction that Earth and its humans make up an infinitesimal speck within a reality comprised of vast, multiple and multiply-dimensioned universes. The acceptance of such a reality raises an obvious and discomfiting question: Would a God that reigns supreme over such a vastness really take notice of an insignificant and presumably backward species such as ours?

The more one reads about the modern scientific understanding of reality, the worse it gets. Arguably the most important scientific advance of the past century is quantum mechanics (QM). The fundamental mathematical equations of this discipline, derived in the 1920s from experimental observations, have been proved accurate again and again, and are the basis for many modern technologies. Yet the physical reality suggested by QM’s equations is severely at odds with the ways in which humans tend to think about themselves and their world. Indeed, the prevailing theory about QM reality is about as cold and nihilistic as any theory could be.

This prevailing theory was originally called the Relative State Formulation by its inventor (a lapsed Catholic named Hugh Everett, who died in relative obscurity in 1982), but is now famously known as the Many Worlds Interpretation (MWI). It suggests that the particles constituting the fabric of “reality” exist naturally not as discrete, individual objects but as what might be called an interconnected multiplicity of states—a ghostly multiplicity that indicates the presence of separate worlds or universes.

In other words, while our reality appears to be constructed of discrete particles, and we generally experience only one world or universe that appears to proceed probabilistically along one timeline, there is in fact a wider reality—a “multiverse”—consisting of an infinitude of other universes.

MWI may be hard to understand if one hasn’t had much physics. But its central idea is that, across the multiverse, everything happens that can happen. In other words, at any moment, the particles that make up any object, including a human, have, collectively, a vast number of immediate futures. These are not possible futures—they all happen/exist, just in different universes. Over short intervals, on the order of seconds or fractions of a second, the differences between these alternate outcomes will be relatively subtle, a matter of slight, seemingly random variations in the positions and other attributes of the subatomic particles making up the object of interest. However, as time goes on—as seconds run to days and years—the differences in outcomes increase dramatically, and of course every branch on this tree of possibility keeps branching again and again, with every femtosecond tick of the cosmic clock. Thus, any person, or any other object, faces at any moment a near-infinitude of futures, and, again, each of these—according to MWI—actually happens in a separate universe within the multiverse.

I’ve never seen any emphasis of this point in popular treatments of MWI, but the theory suggests that the multiverse—all Creation—has a perfect completeness. Its history could be imagined as a closed book on which each page has been inked solid black with the superimposed imprints of innumerable typed and re-typed characters. From the perspective of its godlike author, the book would contain every possible story. From the perspective of an individual human, incapable of perceiving more than one (very brief) timeline, it would contain only the story through which he has lived—though, again, this individual human would really have been only one manifestation of a rather hazily defined collective entity that, from the moment of birth and at every moment thereafter, proliferated into every possible variation of identity and experience.

Whether the ever-branching universes that make up the multiverse are created ex nihil, or already exist—beyond time as it were—in a meta-realm of every possibility (that closed book of over-inked pages) is something that MWI theorists still debate. But the implications for the human self-image are just as dire either way.

In essence, “you” will have been a hero in some of the worlds you have lived through, a villain in others, a nonentity in most. From the perspective of a god who sees all these timelines, do you deserve punishment for your villainy, praise for your heroism, scorn or pity for your nonentity-ness? Wouldn’t such a god understand, instead, that you—far from having any agency in the way that humans instinctively assume—have been fundamentally obliged to be all things, across all your timelines, simply to fill out the full space of possibilities comprising multiversal reality?

And from the perspective of such a god—or of any entity that can apprehend the reality of the multiverse—what are the histories, written or experienced, of myopic humans who think the one universe they perceive is all there is? Do these single-timeline accounts have any more significance than, say, the precise arrangements of handfuls of sand tossed by random children on a beach? These arrangements, these histories, may be influenced by “laws” that relate precedents to outcomes. But the fundamental variability that drives them, collectively, to satisfy every possibility, suggests that their individual significances to an MWI-perceiving god would be nothing—zero.

Does MWI’s final reduction of the “meaning of life” to absolute zero really have dire implications for humanity? Must we believe, with Pascal, that the human psyche has within it an “infinite abyss” that “can only be filled by an infinite and immutable object”? Humans like other animals have evolved, first and foremost, to live and to procreate. Moreover, through medical advances that enable longer and longer lifespans, humans may soon start to see themselves as very godlike.

Yet humans are a contemplative species, and if they can be inspired by contemplating some things, so can they be depressed—even to suicide—by contemplating others. What could be more depressing for them than to become aware of their imprisonment within one tiny solar system, in one vast universe of implicitly zero meaning and significance, inside an infinitely wider multiverse. Hugh Everett himself appears to have felt this conflict and its implications, in the sense that he became an atheist who smoke, drank, and ate to excess—essentially killing himself with a heart attack at the age of only 51—and before he died specified that his remains should be thrown away like garbage.

Beware ETs Bearing Gifts

Humans appear to be bound to confront QM and MWI not only through popular science literature and routine technical education, but also as quantum technology (especially quantum computing) starts to replace conventional technology in many applications—causing users of the new tech to wonder, how does this really work?

Conceivably, modern societies, through some radical cultural shift—perhaps driven by the new and unprecedented cultural power of women—will avoid this confrontation by turning away from science. The elevation of science that we see in the modern West is, after all, a relatively recent cultural choice, one that not every civilization has made. By rejecting that choice, for example as the Amish have, humans could protect themselves from MWI and similar toxic knowledge indefinitely. For now, though, it seems unlikely they will choose such a radical change of direction.

Another possibility we tend to overlook is that humans, whatever their choices, might nevertheless be abruptly forced to confront toxic scientific knowledge, if an extraterrestrial civilization were ever to visit Earth and attempt communication. What is the nature of reality? How is the fabric of existence constructed? Those are among the first questions we would ask visitors from a more advanced, star-faring civilization.

Martin Amis once touched upon this theme in a short story titled “The Janitor on Mars,” which, suffice it to say, was pretty dark in its view of human morale and morality in the context of an encounter with a superior ET civilization bearing nihilistic cosmological revelations. The least dark element of the story was the impending sudden destruction of the Earth and extinction of humans. In real life, humans probably wouldn’t be granted such a mercy, and would have to die off slowly, one by one in “deaths of despair,” and multitude by multitude in suicide cults and wars.

The fact that craft from ET civilizations are, at least, scarce in Earth’s skies, could thus reflect not only a “despair trap” that strangles most technical civilizations in their cradles, but also the awareness—among those fortunate civilizations that have survived the trap—of the potent effect of the knowledge they carry, on such naïve and primitive species as ours.

***