No man is an island.

This short essay was prompted by the debate surrounding the ongoing Russian threat to invade Ukraine. But it is really a more general argument about state-vs.-state conflicts—even human-vs.-human conflicts.

My train of thought here was first tugged into motion when I read some of the remarks by Twitter nomenklatura, to the effect that the US shouldn’t lift a finger to help Ukraine and countries like it, should focus on its own problems, should stop “warmonger” talk, etc.

To me, such arguments reveal not just that a lot of Americans have failed to learn the lessons of history, but also that they’ve lost touch with some of their most basic and useful moral instincts.

(I should note here that I have no “axe to grind” where Ukraine is concerned: I don’t know any Ukrainians; I’ve never been to the place; I probably never will go there.)

Some quick background

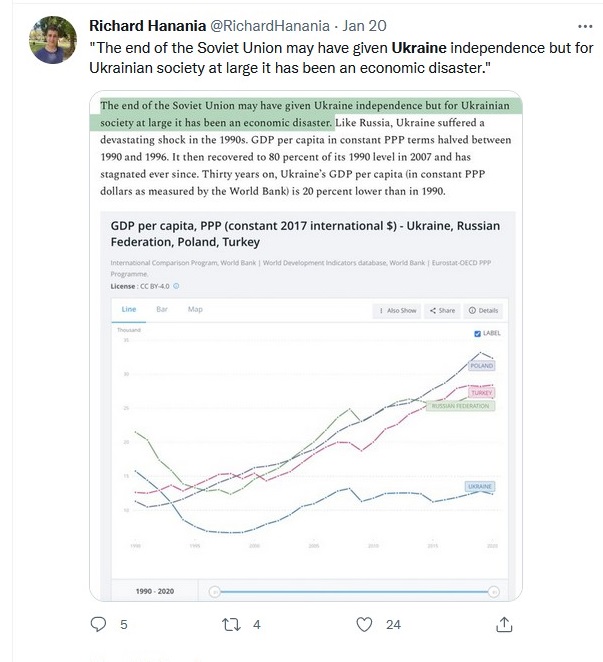

In the 1980s, severe economic divergence between the Eastern Bloc and the democracies of the West, and the related weakening of the Soviet state, led to the emergence of durable pro-democracy movements in Poland, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, East Germany, and other captive nations. These movements came to successful conclusions in 1989, when they brought down the Warsaw Pact, the Berlin Wall, and the entire Iron Curtain. Two years later, the USSR itself disintegrated, its constituent “republics,” including the core Ukrainian, Byelorussian, and Russian Republics, seceding from their union in late 1991. Most of the government offices and instruments of power in Moscow reverted to the control of the newly named Russian Federation, which became, initially, more of an ally than an adversary to the West.

This was, for the West, a victory almost on the scale of the Second World War’s. Indeed, it seemed to bring to a close not just the Cold War but also the broader process of European upheaval that had begun with the start of the First World War in 1914.

But the waters did not stay calm. The first post-Soviet leader of Russia, Boris Yeltsin, was an alcoholic and a clumsy and corrupt administrator, and was forced to resign in 1999. He was replaced by his appointee Vladimir Putin, an ambitious former mid-level KGB officer who had entered politics after the fall of the USSR. Putin had a mess on his hands at first, and had to contend, among other things, with a much more democratic political system than had existed in the old USSR. But he eventually got things under control, in the traditional Russian way one might say—he smothered Russian democracy in its cradle, enriched himself and his cronies, and made Russia yet again an adversary of the West.

Putin never achieved a Stalin level of power, but he had enough control to bully and imprison political dissidents at home, and assassinate them abroad. He also was increasingly able and confident enough to impose Russia’s imperial will on some former captive states that had become too independent-minded, namely, in the oughties, Chechnya and Georgia, and, starting in 2014, Ukraine—following a popular Ukrainian uprising against that country’s pro-Russian leader, Viktor Yanukovych. Russian troops, not very convincingly described as volunteers and separatist freedom fighters, invaded Ukraine in that year, ultimately occupying the Crimean peninsula as well as a resource-rich eastern region called the Donbas.

Now Putin has positioned Russian troops and equipment seemingly for a new invasion, and has issued the West (principally the USA) a set of extreme demands that essentially convey the message: Ukraine is part of Russia, or at least should be forever under Russia’s thumb.

While Putin has acted boldly (by timorous Western standards) against Ukraine, Georgia, and Chechnya, he has not dared to attack other former Soviet satellites, such as Poland, Romania, and the Baltics. There is a simple reason for this: In the wake of the USSR’s collapse, the latter all eagerly joined NATO to protect themselves against their ancestral Russian enemy. Being a NATO member carries the solid-gold guarantee of full military assistance—troops and weaponry—from other alliance members in the event of Russian invasion. This has, to all appearances, been a sufficient deterrent against Russia since NATO’s inception. Ukraine, Georgia, and Chechnya are not members of NATO.

Reasons to Leave Ukraine to its Fate

There are true, mostly unspoken reasons why Americans, and Westerners generally, don’t want to help Ukraine in a decisive way, and there are essentially false, justification-type reasons that are provided for public consumption.

The true reasons are 1) having troops killed and precious military hardware destroyed on behalf of a country that is out on the margins of Europe would be costly—above all politically; and 2) opposing Russia too strongly would interrupt its supplies of natural gas to certain European countries (e.g., Germany) that badly need this resource, which, again, would be politically and otherwise costly.

These reasons strike me as quite similar to the reasons schoolchildren use, or feel, when they observe a bully threatening someone else: Although they at least vaguely recognize the value of stopping the bully, they fear the cost of “sticking their neck out” to fight, and feel that it would simply be cheaper to look the other way. The bullies, of course, understand this reasoning and exploit it.

The public reasons for not supporting Ukraine, a relatively democratic European state facing invasion by an authoritarian semi-Asiatic aggressor, largely have to do with Ukraine’s not being part of NATO, with Russia’s alleged right to control states on its periphery—sometimes referenced with the phrase “sphere of influence”—and with a general feeling that leading Western countries, especially the US, are overextended already and shouldn’t always try to be the world’s policeman. There is even the notion, apparently popular among many right-wing Americans, that Ukraine in recent years has become an American colony, the creation of warmonger “neocons,” and should now be liberated from the American empire so that it can return to the natural, bosomy embrace of its Russian mother.

Reasons to Stand Up for Ukraine

Firstly, the people of Ukraine, despite their ancestral brutalization and periodic annexation by Russia, consider themselves—and are—a distinct Western, Christian people, with their own culture and language. If there is one broad political-philosophical priority that Western societies should stand up for, it is the political independence of their distinct peoples—the same “inalienable right” of self-determination on which the USA was founded.

Secondly, NATO intervened decisively in Bosnia in 1995, to defend the independence of that country from what was essentially an attack by neighboring Serbia as well as by Bosnian-resident ethnic Serbs. What did the beleaguered Muslim Bosnians possess, to justify NATO’s protection, that Christian Ukrainians now lack?

Thirdly, and just obviously, the only broadly applicable and effective way in which small states can protect themselves from much larger aggressors is by joining alliances or other collective security arrangements. Ukraine naturally would like to do this, but for various reasons, including the terminal pusillanimity of Germany (which still flinches when anyone mentions the Red Army), has not been allowed membership in NATO. Thus, the fact that Ukraine is “not part of NATO” is more a cause of Russia’s bullying than a valid justification for acquiescing in it.

Fourthly, the US and Russia in 1994 inveigled Ukraine (along with Kazakhstan and Belarus) to give up the Russian nuclear weapons stationed on their soil, in exchange for various security guarantees, under the so-called Budapest Memorandum on Security Assurances. Twenty-eight years on, Russia has blatantly and repeatedly violated this agreement. The US, though it promised at the time to come to Ukraine’s aid if Russia turned against it, has instead sought to weasel out of any real commitment. However, the agreement was explicitly meant to provide a security assurance—it’s there in the title, folks.

Fifthly, failing to stand up to Putin will embolden him. I notice the mockery some on the right have leveled, not only at this obvious argument, but also at the obvious Munich 1938 comparison. If there’s anything about this debate that really sparks my ire, it’s that smug “you can’t compare now to 1938” stuff. This is not an argument requiring fine, scholarly distinctions between historical events! This is about basic human nature. And, while it’s true that Putin’s aims now might be limited to Ukraine (or mere threats to Ukraine), it’s also true that Hitler’s aims were limited, vis a vis Western Europe, in 1938—but of course his aims got bigger as the threat from those who opposed him got (as he assessed it) smaller. Another way of putting this is that the manly instinct to fight the bully, even at considerable cost, even when the bully doesn’t directly threaten oneself, is not a useless atavism, as some commentators seem to think. It is still an adaptive reflex and, along with antibully systems such as NATO (imperfect as they are) underlies the relative peace of the developed world.

Sixthly, failing to stand up to Putin, allowing him to carry out his rape of Ukraine, will have demoralizing effects on the people of the West. The revealed weakness of the leading Western countries also could nudge any country that had hoped to get the West’s protection to instead become a minion of Russia.

Finally, failing to stand up to hegemonic bullies is a bad long-run strategy, just in simple logical terms. With no credible alliance to oppose him, the bully can subjugate his victims one by one, conceivably until he is too powerful even for an alliance to oppose.

What should have been done?

In general, those in a position to do so should have provided Ukraine with a worthy alliance to join as soon as the country started moving away from Russia. Although Germany and France (which are partly to blame for the current situation) have long opposed Ukrainian membership in NATO, the US and UK should have helped organize an alternative alliance, perhaps including other, highly motivated ex-Soviet Republics. Even now the US could tell Germany: agree to admit Ukraine to NATO immediately or the US will quit NATO and form a new alliance. In any case, the moment Ukraine enjoyed the formal protection of NATO or some other strong alliance, the Russian threat—if so far uncommitted—would recede.

It’s important to emphasize that last point. The purpose of having alliances is to not to be a “warmonger.” It is to deter war by showing the would-be hegemon that he will get a bloody nose if he takes a step further.

In future, it would also be a smart move for the US and other Western countries to encourage their former regular military men to serve as paid volunteers, equipped with gray market hardware, in conflicts like these. The presence or even the possible presence of such experienced mercenaries would be a significant additional deterrent to an aggressor.