A cautionary tale, and a plea for change

“But are you strong enough now for a truly big fish?”

—The Old Man and the Sea

Have you ever had a Big Idea—an idea with the potential to transform the way people think about their society and culture?

Imagine that you had such a Big Idea, but you weren’t a professional opinionator and didn’t have an easy way of getting your Big Idea “out there” in front of a lot of readers.

Imagine too that your Big Idea was going to be controversial enough, in mainstream circles, that publication under your own name would almost certainly cost you your livelihood.

What would you do?

Here is what I did—and, as they say, don’t try this at home.

THE BIG IDEA

Before getting into the timeline of events, I want to emphasize that I have written this in part for the benefit of other, younger writers, who may read it someday and find it useful—as an account of a process that is relevant to their ambitions but seldom set forth in detail. More than that, though, I see this as a “case history” supporting an argument for changes in how we deal with new ideas (of the non-copyrightable, non-patentable variety) and incentivize their originators.

Now to the what and when: It all started early in the new millennium, after I returned to the US following a decades-long sojourn abroad. As I settled in, certain differences in American culture, compared to what I’d known as a young adult, started becoming apparent. Themes of “trauma” and suffering seemed much more prominent in the culture, from media to medicine. Public policy debates were often competitive exercises in projecting compassion, or “empathy,” in regard to supposed victims. Political correctness, a hypersensitive projection of concern for the disadvantaged, seemed out of control. Even in my own somewhat technical line of work, I noticed similar changes in tone and emphasis.

Eventually the proverbial lightbulb winked on. As I put it in an essay (“The Demise of Guythink”) in late 2011:

… these empathy-related changes in public discourse are due in large part to the recent, unprecedented entry of women into public life in Western countries. Women have not only the right to vote but also a presence in key areas of society—science, law, business, politics—as never before, and it would be hard to believe that their influence has not changed the culture, bending it towards their own cognitive style. People now use the jokey phrase “endangered white male” . . . but what may be truly endangered here is the male cognitive style.

That may not be a good thing, if the male cognitive style evolved to be optimal for managing societies, while the female cognitive style is tuned for the rearing of children. There is a tendency in our culture now to treat empathy as a trait to be simply maximized. But “understanding and building systems,” as [Simon] Baron-Cohen puts it, is useful, too—and perhaps most if not all of our culture’s greatest failings now come not from a lack of empathy but from a failure to see how complex systems fit together, and how they may fly apart.

What also worries me is that too much empathy, or other related aspects of the female cognitive style, may be—we don’t know; probably no scientist would go near this question—less compatible with the reasoned debate and calm analytical thinking that are presumably needed in a healthy democracy, or in any mature society. Several years ago, then-Harvard President Lawrence Summers (who was later a White House adviser) referred rather delicately to the possibility that male/female cognitive differences partly explain the relative lack of female professors in math and science; he was, in effect, shouted down and forced from his post….

An inflexible, authoritarian, shout-them-down tendency is often said to be a feature of PC-think generally. PC-driven marches and protests (on campuses for example) typically are meant not to broaden a discourse but, rather, to repel or suppress an unwanted speaker—much as a mother, without any pretense of democracy or debate, would try to protect her children from an unwanted influence or their own innate waywardness. (“Because I said so!”)

There it was: the Big Idea! And it was big! What other theory had the same power to explain the dramatic waves of change that have been sweeping through modern societies in the past few decades? What other theory combined such a simple and compelling framework of understanding with such dark implications for Western civilization?

I posted “The Demise of Guythink” on a website I had set up—of very modest readership—where for several years I had published various short essays on cultural and science-related topics (anonymously, though some readers knew who I was).

As time went on, though, and the novelty and importance of this idea grew in my estimation, I increasingly thought of getting it published more prominently.

The problem was that I had no clear path for achieving that. I wasn’t a complete nobody—as a journalist, I had written a few books, and more than a few newspaper and magazine pieces, including op-eds. But that had been in the relatively distant past. Moreover, as the world had grown richer and the Internet had become a supremely powerful tool, the barriers to entry for becoming a “writer” had collapsed to virtually nothing, creating more competition than ever and making the process of big-media publication, from a cold start, harder than it had ever been. I pitched a roughly 600-word version of my thesis to the Wall Street Journal’s op-ed people around that time . . . and, if memory serves, got the same result one would get from dropping a small stone into the darkness of a mile-deep well.

I might have persevered with other newspapers or webzines, but I soon concluded that that could be an uphill, potentially very costly struggle. The standard line set down by feminist activists—de facto thought leaders for Western women—was that the fairer sex was still hindered, harassed and victimized by all the things men did, and thus needed ever more power to achieve full emancipation and equality. Indeed, it seemed to me that women’s ability to influence men had always depended heavily on their claims to be relatively weak, needing special protection, etc. In other words, in the age-old power contest with males, females’ claims of powerlessness and victimization were basically reflexive and relentless. Thus, my observation that women were already moving past parity and achieving real dominance in many key areas of public life, from teaching and publishing to psychiatry . . . was likely to be dismissed as a fantasy, or, worse, suppressed as a heresy.

My further suggestion that women’s new dominance in Western civilization was hazardous to that civilization, because maternal thinking was not suited to the public sphere, would make this a heresy to be suppressed with extreme prejudice. I imagined screams, shouts and ululations until I was well and truly cancelled and silenced—to the extent that feminists and the Left had to take notice of me. So, publishing my Big Idea prominently under my own name didn’t seem wise, at least not before my retirement, which was still a long way off.

I can’t remember whether I received any direct feedback on the piece I posted on my website—I didn’t have the time or energy to maintain a comments section. But the site analytics suggested that it was read by at least thousands of people over the next year or so. A “manosphere” writer named Matt Forney linked to it in one of his own blog posts. That’s pretty much all I remember about its impact.

SCRATCHING THE ITCH

Years passed. Other events and interests held my attention. It was not until June of 2014 that the urge to write about cultural feminization rose up in me again.

This time I pitched a piece on the subject to Takimag, a small webzine that, although I didn’t normally read it, struck me as suitably uninhibited. The editor, the daughter of Takimag’s proprietor, said she was potentially interested, but wanted it shortened in a few ways. I complied and re-sent it. She then replied simply that she couldn’t use it after all. I was left with no clear idea of her reason, though naturally it occurred to me that pitching this idea to female editors was not an optimal strategy.

Where else could I send it? I figured that if even Takimag—somewhat fringy, and typically framed by the mainstream media as “far right”—wouldn’t touch this hot potato of an idea, and if female editors were problematic, then I’d have to venture still further out onto the fringe. The obvious place was the manosphere.

As a middle-aged family man, I didn’t have much use for “game,” complaints about the contemporary dating scene, or other themes central to that subculture. But the urge to get my idea out there, somehow, anyhow, was strong now. Without much effort (though I again had to shorten my submission by quite a bit), and using a pseudonym as most of their contributors did, I got a new version of my thesis published on Roosh Valizadeh’s Return of Kings site. If you use the Wayback Machine and check the site as of late 2014, you’ll see that the piece was posted in August of that year. (It has also been archived here.) My title was “No Country for Men,” but Roosh or one of his editors, probably for SEO reasons, changed it to “Thanks to Progressivism, America is No Country for Men.”

It was much read and commented upon, within that circle of readers, and for some years it was easily googleable. However, as the mainstream media became more feminized and “because-I-said-so” inflexible, outlets like Roosh’s became less permissible. Ultimately—suppressed by search engines, and with most or all of his monetization routes blocked off—he was forced to shut down. So, although I didn’t see it right away, this was yet another dead-end in my quest.

Posting on Return of Kings did, however, scratch the “get it out there” itch, and another year or so passed before the itch recurred. Using my real name, I pitched a very softened version of my cultural feminization idea to the Washington Post, and surprisingly, the response was not a blank refusal but an invitation to submit my piece for posting in their “PostEverything” section. Looking back, I think I probably should have done that. However, at the time I saw PostEverything as a glorified Letters to the Editor forum, and reasoned that publication there would bring little reward, while leaving me with the usual risk to my livelihood. I guess I also feared that the Post’s editors would alter my thesis in ways I wouldn’t like. So I declined the offer.

I pitched a similar piece to one or two other places around then, and though my records and memories of those efforts have faded, the result was the same. Thus, early in 2017, I reverted once again to self-publication. Using the anti-Trump, pro-feminism Women’s March as a peg, I posted a short presentation of my idea to a blog page on my personal, non-pseudonymous, website where I had posted a few other short essays over the years.

I didn’t keep it up on that site for long. A few months after it was posted, a prospective client of my consulting business, a woman with a moderately high position at a prestigious institution, read it (as indicated by my site analytics info) and immediately ghosted me. I assumed that my thesis, even as softened as it was, was the causative factor in this loss of what could have been a lucrative relationship, and immediately took it down.

We’re nearing the fateful Twitter years, but not there yet. In the Spring of 2018, I submitted yet another softened version of my cultural feminization thesis to Quillette, which was then just emerging as a new and interesting venue for non-woke thought. One of the editors, a fellow named Jamie (Palmer, I think), turned it down politely with the comment that: “Your thesis is interesting but, in the end, unpersuasive and feels like a possible correlation/causation confusion.”

A bit less than a year later, in March of 2019, I sent yet another version of the idea to an editor at the conservative public-policy magazine City Journal, but received no reply.

(As the reader may know already, both City Journal and Quillette have since published pieces offering versions of the cultural feminization hypothesis—pieces that make no mention of me or my essays.)

TWITTER AND “J. STONE”

Once again, failure to get published in other journals led me back to a more D.I.Y. mode of punditry. Later in that month of March 2019, I set up a new pseudonymous website as a home for my essays, and joined Twitter with the idea of using Twitter posts to publicize those essays.

I think my general idea was to be a proponent of “cold logic” over the “hot emotion” of a feminized world, so I used the domain absltzero.com. For my Twitter presence I invented the pseudonym “J. Stone,” which had the merit that it didn’t seem like a pseudonym.

Having posted a quick version of my thesis, titled “The Great Feminization,” on the new site, I joined Twitter and started using my tweets to advertise the essay.

What happened next? Crickets.

At the time, I didn’t know much about the process of drawing attention and followers on Twitter, and anyway was unable to spend much time on it, given my day-to-day work and family responsibilities. But I did try, at least several times per week, to reply to tweets from prominent Tweeters with relevant quips followed by a link to “The Great Feminization”—in the hope that one, eventually, would read it and recommend it to his or her flock of followers.

“The Great Feminization,” by the way—though it was broadly similar to others I’d written, going all the way back to “The Demise of Guythink” in 2011—did contain a fairly pithy summary of the situation:

Feminists these days spend a lot of time worrying about male-dominated culture—“patriarchal culture,” “sexual harassment culture,” “rape culture,” “the culture of silence,” and so on. But shouldn’t they be acknowledging the influence that women now have on culture: on workplace culture, on media culture, on campus culture, on American culture, and on Western culture generally? That feminizing influence may be the greatest single driver of the rapid social changes seen in recent decades.

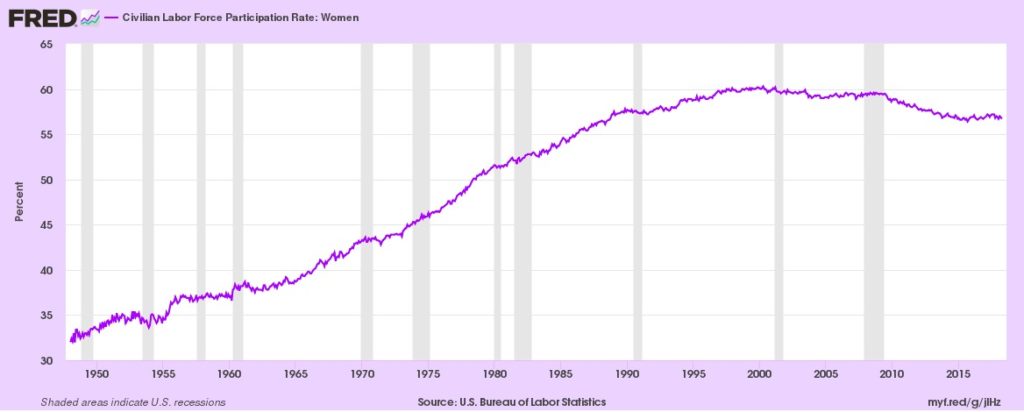

Consider the following U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics chart of women’s civilian labor force participation rate.

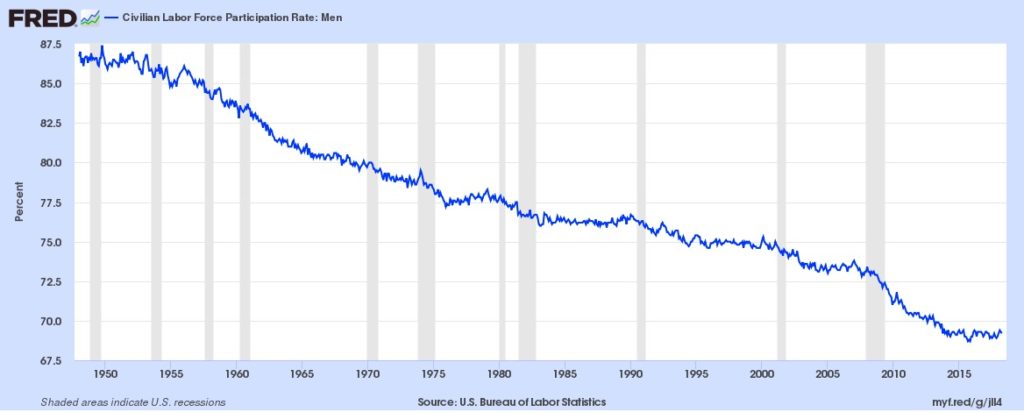

It shows that in 1950 only about 30 percent of working-age women were in the workforce, but by 2000 that figure had jumped to 60 percent and rivaled the participation rate for men, which had been in decline since the early 1950s.

In other words, by 2000 the U.S. workforce had been mostly gender-integrated. On average, workplaces by then had almost as many women as men.

The historic significance of this migration on its own appears to have been underappreciated. Women never made such a move, to such a degree, in any large human society in the past. It significantly altered the structure of ordinary life.

But women in the late 20th century didn’t just move into the workforce. They moved into its upper ranks, to professions that strongly influence societal culture and policy. They became journalists, public relations specialists, lawyers, academics, novelists, publishers, filmmakers, TV producers, and politicians, all to an unprecedented extent. In some of these culture-making professions, by the 1990s and early 2000s, they had achieved parity or even dominance (e.g., writers, authors, and public relations specialists) with respect to men. Even where they fell short of full parity, they appeared to acquire considerable “veto” power over content. A 2017 report by the Women’s Media Center noted evidence that at the vast majority of media companies, at least one woman is among the top three editors.

Why is the greater presence of women in culture-making professions important? Because women, on average, think differently than men on a wide range of subjects….

How would culture and policy have changed as a result of women’s new influence? Presumably in ways that reflect feminine psychological traits.

For example, women appear on average to be more empathetic and compassionate, more emotionally sensitive. Some of the most striking social changes of the last few decades appear to have been driven by a cultural shift in that direction:

-

-

-

- More generous welfare programs

- Expansion of the concept of welfare to include more types of intervention (affirmative action, etc.) and more groups needing intervention

- Expansion of the definitions of “harm,” “offense,” and “trauma” (“microaggressions,” “triggers”)

- Increased attention to psychological trauma in law and medicine, leading to a greater acceptance, and thus a higher prevalence, of trauma-related syndromes such as PTSD (and the recovered-trauma-memory syndromes of the 1990s)

- Less tolerance of deaths in war; but, ironically, a greater inclination to enter foreign conflicts in response to emotion-evoking atrocities portrayed on television.

-

-

-

-

-

- Less tolerance for capital punishment

- Less restrictive immigration policy

- More emphasis in media and policy contexts on emotion-evoking stories of individuals (e.g., pitiable refugee children) rather than dry analyses of long-term outcomes.

-

-

-

-

-

- Suppression of any kind of emotionally disturbing speech (“hate speech,” “mansplaining,” etc.) and even fields of scientific inquiry that are likely to evoke negative emotions;

- Less affinity for traditional, constitutionally protected forms of confrontation in the legal and political spheres, i.e., less support for open debate, free-speech rights, and “due process of law.”

- Suppression/replacement of words that evoke emotional discomfort (e.g., “abortion clinic” becomes “women’s health center”)

-

-

That’s just from one set of closely related traits. Certainly there are others. For example, women for obvious evolutionary reasons appear to have an instinctive fear of dietary and environmental toxins, which can become pronounced during pregnancy (“morning sickness,” nesting reflex, food aversions). Is it just coincidence that women’s cultural ascendancy in Western countries corresponds to a huge rise in diet-, drug-, and environment-related concerns encompassing the Green movement, anti-GMO attitudes, “detox” fads, the “herbal medicine” racket, “organic foods” preferences, and even the anti-vaccine movement?

Et cetera. It was a quick, accessible outline of my Big Idea, and I gathered from my website analytics that people who started reading it tended to read it through, and often sent their friends links to it.

Still, the daily reader count seldom got into three digits, and sometimes flatlined in the single digits for days at a time, especially if I was too distracted by work to do my reply-guy thing on Twitter. For weeks, and then months, my interest in the whole thing waned, as it just seemed unrewarding.

But the compulsion to get some recognition for my Big Idea was one of those relapsing/remitting conditions that can never be fully cured. Within six months of posting “The Great Feminization,” I began work on a new cultural feminization essay, centered on a more in-depth account of the aforementioned Larry Summers brouhaha.

I initially conceived of this essay, which came to be titled, “The Day the Logic Died,” as something that would be publishable in a respectable conservative venue. But by the time I’d finished it, and weighed its largeish word-count, I knew better, and just posted it to the absltzero.com site.

“The Day the Logic Died” was an exploration of the Larry Summers case as a classic early example of a cancellation hysteria created by activist, anti-rational women in academia and media—a classic demonstration, in other words, of cultural feminization and its unpleasant consequences. I also put in a hypothesis at the end about the deep reasons why men fail, again and again, to hold their own in this new female-controlled cancellation culture. Though it was a long essay, it was probably the most “writerly” one I’ve produced on this topic.

Once again, not much happened in the weeks after I posted it. But a few months later, lightning finally struck, and—using my reply-guy strategy—I succeeded in getting “The Day the Logic Died” noticed by a popular Twitter figure. This was the celebrated “Spotted Toad” (@toad_spotted), who read the essay, liked it, and recommended it to his tens of thousands of followers:

Boom. The essay went “viral,” as they say—Statcounter began registering thousands of hits per day. And as people checked my posts and my bio and saw that Spotted Toad followed me, I began accumulating many more followers. To my surprise, many of these were Twitter-famous or even real-life-famous people with high follower counts of their own. They included Wesley Yang, Walter Kirn, Nick Denton, Marc Andreesen, Helen Andrews, Micah Meadowcroft, and Steve Sailer. One of the best known of these even DM’d me, wanting to know—apropos of the Larry Summers essay—if I was on the faculty at Harvard.

Naturally, this positive reaction encouraged me to spend more time on Twitter, and to keep posting essays on absltzero.com, including essay #3, “Girl Power” (Jan 2020), in which I tried to trace the roots of modern cancel culture back to convent hysterias, Salem, and other female social contagions of yore.

Writing more, both in short-form and long, was probably unwise at this point, given how little time I had to spare for it. But anyway I pressed on, publishing additional essays whenever I felt I had something reasonably new to say.

STONE’S PEAK

Early 2020 brought the COVID crisis. Fear of what the pandemic would do, anxiety over the sudden economic shut-down, and stress over lockdown and mask-wearing rules combined to exacerbate the national frazzlement. Then in the approach to the presidential election, Democratic Party operatives’ stoking of black grievance and white guilt—achieved by pumping several police run-ins with recalcitrant African-Americans into national prominence, and organizing marches and riots—was added to this toxic mix. As I pointed out often that year, mostly in tweets and once or twice in essays, stressed American women had reached a sort of breaking point, causing them—in a social mania akin to the Chinese Cultural Revolution of 1966-76—to shift their society-disrupting activities into a higher gear.

This contagious frenzy, which Sailer aptly called the “Great Awokening,” was essentially female in a way that, I thought, made the concept of cultural feminization increasingly obvious.

Throughout 2020 and early 2021, the COVID-19 pandemic kept me busy professionally. I did find time to change the domain name of my essay website from absltzero.com to thoughtsofstone.com. I also probably made at least one or two further—now-forgotten—efforts to get published more widely. But those too failed, and by April of 2021, I was getting restless again.

At this point, I had enough big-name Twitter mutuals (who were routinely liking and retweeting my stuff, and reading my essays) that I felt I could ask for their help in reaching a wider audience. In April 2021, I contacted Helen Andrews, a young author and editor/writer for The American Conservative magazine, to see if TAC would be interested in running a short piece on my cultural feminization idea. Based on her tweets, Helen had struck me as very sharp-minded and conservative—and she was clearly enthusiastic about my Big Idea.

She was gracious in her response, reiterating her support for my thesis and heaping particular praise on “The Day the Logic Died.” After making inquiries, she informed me that The American Conservative as a rule would not publish something by a pseudonymous author. As an alternative, though, she suggested The American Mind, a webzine produced by the Claremont Institute, and she helpfully put me in touch with its editors James Poulos and Spencer Klavan. My short piece on cultural feminization, “Pink Shift,” appeared in TAM’s pages in early May.

Naturally, I felt that this was progress, in the sense that I was reaching a wider readership, and was also basically putting down a public marker of my role in advancing the cultural feminization hypothesis. But though I gained a modest number of new Twitter followers and daily readers of my essays, I was still far from my goal.

Months passed, and the familiar, unpleasant sense of futility grew in me. I had made a reasonable effort—especially given my work and time constraints—to get my Big Idea “out there” and noticed. Certainly a lot of people, in a strong position to help, were well aware of it and its provenance. But how could I propel this idea into the public mind strongly enough that it had to be confronted and considered, and never again ignored or suppressed? And what more could I do to get the recognition I felt I deserved? Whatever the true answers to those questions may have been, I did little other than what I had been doing, namely writing to small-ish media organizations and asking them to publish my Big Idea.

That strategy continued to not work, although for a while, things kept happening to prop up my hopes. One day in mid-October 2021, I did a routine check of the analytics for the thoughtsofstone.com website, and saw thousands—soon tens of thousands—of visitors to the “Great Feminization” essay page. It was clear that all these visitors were arriving via a link on a blog called Marginal Revolution.

Marginal Revolution is the blog of Tyler Cowen, the economist, Bloomberg columnist, and all-round social media star. I wasn’t entirely surprised that “The Great Feminization” had caught his attention, as I had observed in the past that his ideas and mine sometimes ran in similar (at least marginally heretical) directions. We had even had a brief, cordial email exchange during the 2008-09 financial crisis—when he was already very popular, but far more approachable—in relation to one of my ideas (on my anonymous blog) about the future economy.

In any case, Cowen’s link to “The Great Feminization” widened the essay’s circulation not just for one or two days, but for weeks and months—in which many other bloggers and posters cited it approvingly, and visitor counts at the thoughtsofstone.com site stayed high.

Toward the end of that month of October, energized by the Cowen link, I pitched another piece on cultural feminization to Twitter mutual Park MacDougald, a young editor/writer at the Washington Examiner. He told me he was just then bound for a new job at UK’s UnHerd, but would try to get the piece in before he left, if I could get it to him quickly. I did, we did some rapid edits, and on Oct 27 he told me the piece would be online two days later.

The piece—my working title was “Wokeism is a Woman”—didn’t really include anything new compared to what I’d already written on the subject. It started as follows . . .

Consider the hypothesis that most of the dramatic social changes sweeping over Western societies in recent decades, including the rise of social justice ideology or “wokeness,” are driven not so much by a specific ideology as they are by a simple demographic shift, namely, the large-scale addition of women to the ranks of the elites.

It is curious that this possibility has been overlooked for so long. Since the middle of the last century, women in the West have almost completely departed from their traditional stay-at-home roles. They have moved into the workforce alongside men, and have acquired power, often dominance, within all the culturally and politically influential professions. Women are now managing editors, film producers, CEOs, university presidents, cabinet secretaries, senators and congresswomen. They now help direct the culture and the policies that move all of us—the first time this has happened in a large society.

. . . and it ended (in the last draft I have in my files) this way:

In any case, the most important issue about this “great feminization” is where it appears to be taking us. Do we really want to jettison things like due process and free scientific inquiry? Do we really want laws discriminating against America’s legacy population, especially white males, in the name of “equity?”

I suspect that a lot of people, men in particular, already sense at least subconsciously that wokeism and related social changes reflect the new power of women—and hope that the worst of these changes are a sort of emotional storm that will blow over eventually if they just ignore it. I think that view overlooks, to put it mildly, wokeism’s sensational recent successes in transforming Western societies, and its strong roots among the women who help run those societies. Wokeism is too incoherent, too contrary to common sense and human nature, to last anywhere near as long as Western liberalism has. But rolling back its excesses is going to require real effort. Step one should be the recognition—as harsh as it may seem—that wokeism, far from being an enlightened vision of human progress, may be only the projection of a maternal mindset that is dangerously out of its depth.

THE SHARKS

The day before the Washington Examiner piece was scheduled to appear, MacDougald DM’d me to let me know it had been put on hold. I knew that I hadn’t pulled my punches in the piece; moreover, I had experienced one or two last-minute cancellations of pieces in my earlier career as a journalist. So I was not especially surprised when, a week later, MacDougal informed me that they weren’t going to run the piece at all—and that he, about to exit, had little say in the matter. (He offered a kill fee, which I declined.)

It soon became clear that that had been my last chance to get my Big Idea out there and get credit for it. The “Great Awokening” had made women’s central role in wokeness and modern progressivism hard to ignore—and with that (and to some extent the influence of my own essays) other writers with easier paths to high-profile publication were starting to see an opportunity. Other than Cowen with his comment-free linking to “The Great Feminization,” none of them would acknowledge my prior contributions.

Less than a month after my piece on women and wokeness was killed at the Washington Examiner, the writer Noah Carl published a short Substack post (“Did Women in Academia Cause Wokeness?”) arguing that the roots of wokeness lay in the feminization of academia—essentially a much narrower (and I would say incomplete) version of my own argument.

A very similar piece by Mary Harrington appeared on the same day, Nov. 24, in the UK webzine the Critic, about “The New Female Ascendancy” in academia—in the administrative ranks, at least.

Less remarked on is the sex breakdown of the growing proportion of administrators. A recent diversity and inclusion report by the University of California indicates that women make up more than 70 per cent of non-academic staff across (among others) nursing, therapeutic services, health, health technicians, communications services roles, and a majority or near majority across all non-manual staff roles. In other words, if men are still over represented in top academic roles, the non-academic supporting ecosystem is overwhelmingly female.

And that support system has an increasingly symbiotic relationship with student activism, which over my lifetime has (on both sides of the Atlantic) shifted noticeably away from a focus on material conditions toward something more like the bureaucratic regulation of personal identity and interpersonal interactions.

A 2015 look at student protesters across 51 campuses showed the most common demands — alongside greater diversity among faculty — were diversity training and cultural centres. In turn, this focus requires a ballooning staff tasked with managing identities, or variously supporting or disciplining types of relationship, for example via “consent” education: the roles where women predominate.

Overseas at the time, I was alerted to the appearance of Harrington’s piece by a nice Twitter DM from Helen Andrews:

Certainly I agreed that I deserved credit! However, as I replied a bit morosely to Helen (after thanking her again for her help and encouragement), I knew that I probably wasn’t going to be given a lot of credit, given that I was a pseudonymous, non-professional essayist with no high-profile publication of my thesis. Again, it would turn out that even a little credit was more than I should have hoped for.

Surprisingly, one of the writers who advanced cultural feminization as his own big idea was Thomas Edsall, a writer for the New York Times, who managed to get a stealthily subversive essay on all this (“The Gender Gap is Taking Us to Unexpected Places,” 12 Jan 2022) into the Gray Lady’s pages. He quoted Tyler Cowen enough to suggest that he read Cowen’s “Marginal Revolution” blog—which to me also suggested that he had read “The Great Feminization” and that his essay might even have been prompted by it. But if one is writing a column for a woke media organ like the New York Times, where young, female and nonwhite activists are always looking for ways to advance by displacing white males, it would be deeply imprudent to cite a pseudonymous essayist who evidently hated wokeism and other leftist dogmas. Of course, from my perspective it would nevertheless have been the correct, honorable thing to do; but I think it’s fair to say that in American journalism now those old-fashioned ethics count for very little. Anyway, Edsall mostly stuck to the quoting of relatively dry academic and survey stuff on gender differences in attitudes, which itself was not new.

. . . a Knight Foundation survey in 2017 of 3,014 college students asked: “If you had to choose, which do you think is more important, a diverse and inclusive society or protecting free speech rights.”

Male students preferred protecting free speech over an inclusive and diverse society by a decisive 61 to 39. Female students took the opposite position, favoring an inclusive, diverse society over free speech by 64 to 35.

I’ll just list briefly a few of the other relatively prominent writers who started posting on cultural feminization, generally with the conceit that they were making an original contribution:

Richard Hanania. Having discussed cultural feminization as a podcast guest in August 2021, he posted one or two Substack pieces on the same topic early in 2022, with arguments very similar to my own. He was already vastly better known than I, but there was a significant overlap in our Twitter mutuals and general interests, so our stuff would have appeared on each other’s timelines quite a lot during 2019-2021.

Some of the commenters on Hanania’s Substack posts also linked to my older cultural feminization essays, which directed at least hundreds of his readers, and I would guess Hanania himself at some point, to my work. I couldn’t help noticing that someone in Southern California (where Hanania lived then), often using an IP address at UCLA (where he had recently been a grad student), was a frequent reader of the essays on my website. Yet as far as I know, Hanania has never acknowledged my prior contributions. (I have previously criticized Hanania for his promotions of eugenics, Vladimir Putin, the Chinese Communist Party, abortions to prevent Down Syndrome births, etc.)

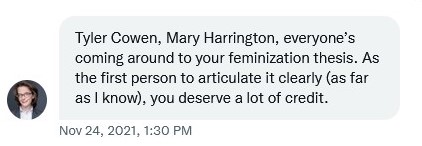

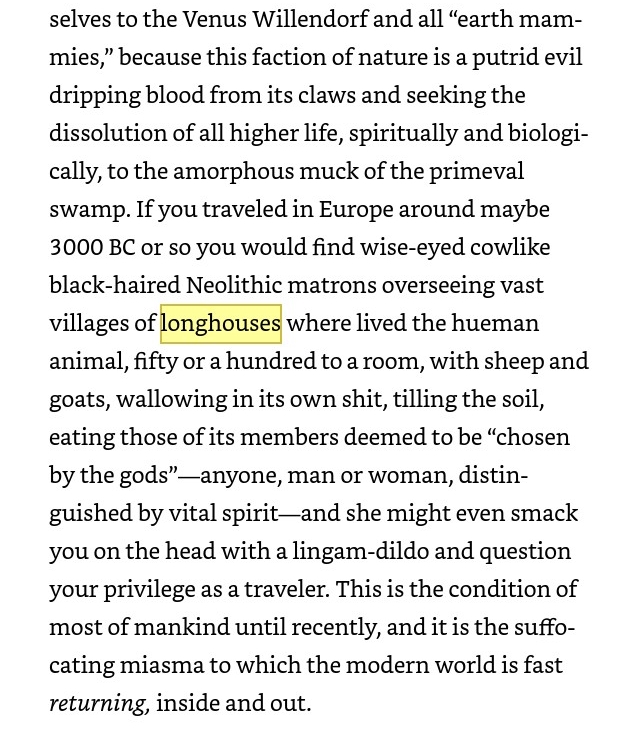

“L0m3z.” This pseudonymous right-wing writer, prominent on Twitter, managed in early 2023 to get a few-hundred-word piece published in First Things (one of the many media orgs on whose deaf ears my pitches had fallen) framing the cultural feminization hypothesis as the “longhouse” theory—a reference to longhouse-dwelling primitive societies.

The idea apparently derives from the book Bronze Age Mindset (2018) whose pseudonymous author’s references to it are pretty cursory.

. . .

None of that is really important anyway, since the invocation of putative longhouse-based societies clearly fails—or is just unnecessary—as an explanation for cultural feminization. Western culture has been feminized mainly because women, abandoning their traditional homemaker roles at the behest of feminists and for financial reasons, have moved into public life and have achieved critical masses in all important, culturally and politically influential Western institutions. L0m3z basically admitted this in his short piece, though he referred to other, later writers like Hanania and Edsall as having pointed this out, not to me. Like Hanania, L0m3z had had a lot of Twitter-mutual overlap with me, and, I seem to recall, followed me for a few months after Spotted Toad gave me some publicity in 2019. L0m3z also didn’t start writing on Twitter about his “longhouse” idea (judging by Twitter searches) until late 2021.

Heather MacDonald. I had always admired MacDonald’s writing, so I was disappointed to see her piece in Urban Journal in March 2023 about the feminization of academia. It seemed unoriginal from my perspective—and, I guess, also would have seemed that way from the perspective of Harrington or Carl. Worse, the initial title appears to have been “The Great Feminization of the American University,” so that, following the publication of her piece (which of course did not cite me) the Google search ranking for my “Great Feminization” essay of 2019 was obliterated, and readers searching for those keywords were directed to MacDonald’s piece instead. (The fact that Urban Journal changed the title hints that someone tipped them off to the existence of my essay.)

There were a number of other pieces discussing this topic, including one in Quillette, and even The American Conservative. None of these pieces mentioned me. No one mentioned me, apart from a few tweeters in replies and blog commenters.

As time went on, and tardier but better-known writers’ thoughts on this circulated more widely, even people who definitely knew of my work started referring to me only alongside, sometimes even after, those other writers.

Of course I know that to the ones making these references, this “inclusivity” would have seemed perfectly natural, perhaps even generous towards the nobody J. Stone. Nevertheless, I felt at least a twinge of annoyance every time. “Nothing these other writers are telling you about cultural feminization is original in the slightest!” I wanted to shout. “That would become instantly obvious if any of them had the decency to cite my work!” But I knew that no one cared–I knew I was dealing with social forces just as inexorable and irrational as the ones I’d been writing about in my cultural feminization essays.

I continued to post occasional cultural feminization-related thoughts on Twitter . . .

. . . but over time I was, as they say, airbrushed from the picture.

It did not help that I was pseudonymous and intent upon remaining so. It also emphatically did not help that, early in 2022, I tweeted/posted in support of Ukraine’s struggle to withstand Russia’s invasion. A large number of my Twitter mutuals, flying flags I had not known they possessed, revealed themselves to be supporters of Putin or at least derisive skeptics about Ukraine’s ambitions to be a free country. I expressed my own derision in regard to this bizarre, anti-liberty, anti-self-determination attitude, and this resulted in my being unfollowed or muted by many. That the facts on the ground in Ukraine increasingly supported my view probably only hurt me worse in this respect.

In 2022, it was increasingly clear from the dwindling engagement of my tweets that I had essentially lost my audience. In April of that year, less than 12 months after my “Pink Shift” piece had appeared in American Mind, I organized my thoughts on cultural feminization into a self-published ebook, as a sort of tombstone for my eleven years of promoting this idea, and then mostly ceased writing about it. I had come to the conclusion that trying to introduce and get credit for an important new idea, from a standing start, on Twitter or a personal website—or on any venue with a small audience—was a mug’s game, little better than shouting to passers-by from a proverbial soap-box.

A BETTER WAY?

Is this just my own personal gripe—my own self-driven, bad-luck story—without relevance to the wider problems of society? I can easily believe that members of the “opinionator elite,” as I call them, would say so if pressed.

I also think that the vast majority of people, even highly educated people, don’t consider the process I have described significantly problematic. They encounter new ideas all the time, and they generally don’t care about recognizing these ideas’ exact provenance—they don’t see that as affecting their interests. Sure, they’ll pile on the opprobrium if a plagiarist is caught red-handed. But if some pseudonymous nobody complains about his prior work being copied and/or not cited by some mass-followed elite opinionator, the latter and his followers will scoff together at Mr. Nobody’s presumption.

That doesn’t mean they’re right! Consider the distribution of forces here: Firstly, there are the opinionator elites, the gatekeepers of media content and popular intellectual discourse. Obviously, they have no interest in finding fault with a situation that empowers them, and to some extent enriches them. Just as obviously, the great mass of ordinary, non-idea-originator people are not going to see a problem if the elites won’t highlight it for them.

Against this weight of opposition and inertia, we amateur, non-elite idea originators—surprisingly numerous but still constituting only a tiny minority in the grand scheme of things—have little chance.

There is also a general misconception that new ideas of the type I’m referencing here—ideas that appear in media outlets like the ones I’ve mentioned in this story—do not deserve protection because they are of a different nature than the ideas or intellectual works we do normally protect, e.g., with copyright and patent laws.

But while it may be true that the idea “cultural feminization is happening and is caused by women’s entry en masse into culturally influential institutions” is not a patentable invention and is not a book or film that can be copyrighted and sold commercially, nevertheless:

-

- This idea has social value in the sense that it potentially explains many otherwise inexplicable sociocultural changes. It may not (yet) have the same perceived importance, but it belongs to the same broad category as Darwin’s theory of biological evolution, and Dawkins’s theory of cultural memetics;

- This idea certainly can have commercial value for writers who successfully negotiate book and/or magazine deals—perhaps even lucrative sinecures at think-tanks—by claiming to have originated it.

Although I think the mechanism by which non-elite idea originators are disadvantaged is essentially non-rational—a blunt-force social suppression—I can imagine a semi-compelling reasoned case for the status quo, which would go something like this:

People won’t believe that a new ‘Big Idea’ is valid unless the author of that idea has plenty of social support, e.g., from a substantial number of authoritative figures (i.e., elite opinionators) and/or a large mass of social media followers. Thus, the introduction of a new idea must be, to some extent, a popularity contest—which means that one must develop a sturdy network of social support before one can expect the idea to spread widely and proper credit to be given. In most cases, gathering such support requires one to write under one’s own name, instead of hiding behind a pseudonym—this is why so many media organizations refuse to publish pseudonymous authors. In short, you can choose to play the game, with a chance of winning, or you can choose to quit and be a loser.

I believe that this would seem reasonable to many people. But really it is not a very good argument.

Firstly, this “social network argument” enmires itself in, or at least fails to take account of, a logical fallacy called the genetic fallacy. This fallacy is the belief that the genesis of an idea has anything to do with the idea’s validity. In other words, if Adolf Hitler had once claimed that two plus two equals four, it would be illogical for us all to disbelieve it merely because Adolf Hitler stated it.

The Hitler example makes the fallaciousness obvious, but in everyday cases it’s not so obvious. In fact (as I would say my own case illustrates) it’s common in public discourse for a good idea to be rejected or ignored, without any consideration of its merits, because the idea-originator is either unknown or—as is true for a lot of conservative thinkers nowadays—somehow intolerably heretical, from the perspective of media gatekeepers.

My guess is that, despite our gatekeepers’ now having more formal education than ever, they are more prone than ever to stray into this fallacy, because there are more women than ever among these gatekeepers, and (for that reason) the culture itself is more feminized than ever. Women, on average compared to men, are drawn more to the personal, less to the abstract, and so they are more likely to consider the character or politics of a person who is voicing an argument before they consider the argument on its merits. In my experience, a shocking number of educated women do not see the genetic fallacy as a real fallacy. Indeed, the modern wokeist/feminist contention that gender and ethnic identity determine the validity of one’s ideas and contributions is a bold assertion of this view.

Now, of course I recognize that we can’t all be abstract logicians. We are social animals, only a few million years removed from our tree-dwelling ape ancestors, and we tend to make decisions in crude ways, often involving associations that are practically useful but not necessarily linked by causal mechanisms. We are disinclined to listen or read when some unknown or fringe-y person starts pontificating—yet the same idea, restated by a mainstream thinker, will be much more likely to get our attention. This does seem natural to us.

Natural doesn’t mean optimal, though. Keeping slaves and burning heretics are among the many practices that once seemed natural to us humans. In more traditional, “natural” times, we also had no protection for—or even concept of—intellectual property. The fact is that current social structures and dynamics governing the treatment of new ideas end up suppressing many true idea originators and rewarding fake ones. Who really believes that we can’t come up with a better, fairer, more modern approach?

It seems worth emphasizing here that one of the great revelations of modern electronic social media platforms, especially Twitter, is that there are surprisingly many amateur but bona fide originators of useful ideas. Obviously it would be good if these people—whether one wants to include me in their ranks or not—had an easier time making their new ideas visible or at least getting credit when their ideas do eventually begin to circulate. This would encourage more new ideas, whereas the present system (as my case is meant to illustrate) discourages them.

Amateur idea originators are, in my opinion, mostly people whose quirks of genetics and life experience cause them to perceive the world a bit differently than the average person does. This doesn’t necessarily make them smarter than average, but it does allow them to see patterns that others don’t. This cognitive differentness (not the same as autism, though very mild autism sometimes produces a similar phenomenon) often puts them “out of step” with their fellow humans not just intellectually but also socially. Thus, in my estimation, amateur idea originators are often among the least equipped and inclined to climb the greasy pole to win social support.

How to amplify their voices? How to give them credit and thereby encourage their contributions?

The Internet already gives us the basic medium for the essentially costless publication of new ideas. Some of us set up our own websites; others have Substack accounts. It should also be possible to craft search algorithms specifically to find and date instances of a given idea on the searchable web—this would seem an excellent application of current AI technology.

It should be possible, as well, to make an “idea registry,” maybe something like a cross between rXiv.org and Wikpedia, to which anyone can contribute, and where ideas are automatically categorized and time-stamped.

I have two basic models in mind. The most obvious one is the patent system, a modern, logical, merit-based system that does not require inventors to garner social support. And, again, while the commercial potential of technical inventions drove the establishment of the patent system, and political/cultural ideas tend to have less money-making potential, the reality nowadays is that new ideas are more monetizable than ever through books, magazine articles, Substack subscriptions, and so on. I also think most experienced professional journalists and opinionators would admit that it is absolutely routine for better-known writers to “borrow” the reporting and/or ideas of lesser-known writers and monetize them with large publishing contracts. Although, again, the average person doesn’t care, quite a few big-name writers would not have their fame and fat incomes but for opportune appropriations of others’ work.

We may not want to treat new cultural/political ideas as protectable intellectual property in the strict sense, by fining violators, requiring licensing, etc. But having an easily searchable record of the originations of these new ideas would, at least, tend to discourage the rampant theft that now takes place.

The other model I have in mind is the “motif index” made by folklorists. Such an index—somewhat akin to patent examiners’ taxonomies of technologies, and zoologists’ taxonomies of plants and animals—is a hyper-branchiate ordering of folkloric tales according to the functional elements they contain. If such a vast and useful information structure could be built by a few folklorists using pre-Internet, pre-computer technologies, it should be doable much more easily now for new ideas in the Internet age.

I see no downside for this general proposal to “level the playing field” for idea-originators. It seems like a no-brainer, really, and my guess is that, as it becomes easy to implement in the AI age, it will happen, overcoming the predictable opposition/suppression by the elite opinionator class. Perhaps I will even get some credit for the idea!

* * *