Thoughts on trauma-tale and cancellation cascades

__________________________________________

From the late Renaissance to the early Industrial Age, it was common for European families to send their adolescent daughters to convents for long periods, in order to educate them, to let them become nuns, or just to keep them out of trouble. The experience must have been something like Girl, Interrupted, but with lots of medieval-style Catholicism, stone walls, and cold baths. Not too surprisingly, the prison-like concentrations of stressed, sexually maturing girls began incubating epidemics of hysteria, often with florid sexual aspects. Also unsurprisingly, given the mystical and demonological themes that were prevalent in Christian cultures of the day, the epidemics generally took the form of “demonic possession.”

Sometimes these episodes stayed within convent walls, and either burned out from lack of attention or were broken up by the dispersal of the participants. But in some notable cases recorded in the history books, convent hysterias had significant impacts beyond the convents, namely when the victims blamed their possessions and/or sexual activity on a male priest. Usually this was the priest who said Mass and heard confessions at the convent, and the claims would be that he had either directly debauched his victims, or had done so remotely via priapic demons. These accusations and the acting-out behaviors that went with them could be competitive and contagious among convent girls, resulting in lurid claims even against men they had never met.

One of the most notorious of the convent hysterias began in about 1632 when an epidemic of supposed demonic possession swept through an Ursuline convent in Loudoun, France. The affected young women claimed that they had been possessed and sexually abused by demons sent by a local priest, Urbain Grandier. He was not the convent confessor, and could not have done the things alleged, but he was good looking and wealthy, and was rumored to be a ladies’ man, counting women in several prominent local families among his conquests. Later historians and writers, including Aldous Huxley, who novelized the story in The Devils of Loudoun, suggested that the convent’s Mother Superior, the index case in the hysteria, knew of his exploits and had developed a sexual obsession with him.

To the initial investigators, there was ample evidence that the “demonic possessions” and associated claims against Grandier amounted to hysterical fantasies. But there was also a political dimension to the case: Grandier on an unrelated matter had recently made an enemy of the powerful Cardinal Richelieu, King Louis XIII’s right-hand man. On Richelieu’s authority, a new investigation was set up to reach the “correct” verdict and suppress contradictory evidence.

To this end, there were public exorcisms of the possessed nuns. These were fantastic displays in which the women, reportedly well coached by Richelieu’s minions, mimed sexual acts while loudly accusing Grandier of various demonic crimes. Thousands of townspeople and even tourists attended these spectacles, and, no doubt as Richelieu had hoped, many considered the nuns’ antics to be convincing evidence of Grandier’s guilt.

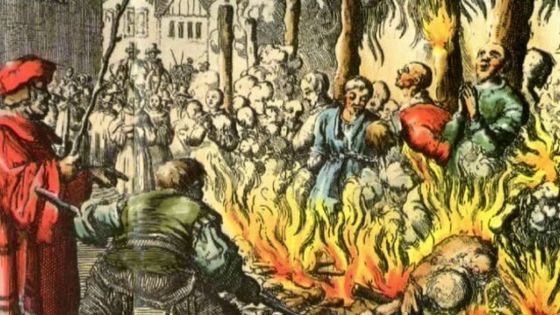

Eventually some of the affected nuns, including the Mother Superior whose antics had set off the whole hysteria, had second thoughts and publicly recanted. Unfortunately for Grandier, the case had acquired too much momentum by then, and he was found guilty, tortured, and burned at the stake in 1634.

The cascade

Some might see witchcraft/possession hysterias like the Loudoun case as just historical oddities, of no relevance today. But I think they belong to an ancient, recurring pattern. After all, outbreaks of sexual-victimization claims among women, and the exploitation of those outbreaks by authority figures, seem as prominent now in the West as they have ever been. Think of the recent Kavanaugh hearings and the public parade of his accusers with their lurid, weepy tales. Think of the Weinstein, Epstein, and Cosby media/legal circuses. This is hardly ancient history!

The idea I sketch out here is that there is a behavioral program, for the most part specific to females, that evolved long ago as an alternative means of empowerment or self-expression but continues to manifest in various ways and indeed accounts for a good deal of contemporary social history.

My argument is basically impressionistic and tentative: I perceive, rightly or wrongly, a pattern that underlies seemingly different social phenomena. I am aware that this is not a terrain that has been or is likely ever to be mapped definitively with social psychology experiments. It is too complex, too squirrelly. It is also much too threatening to current orthodoxy to be a subject of truly free scientific inquiry. So I won’t attempt much more here than to point to cases, describe the apparent pattern, and hope the evidence accumulates enough—in the telling, and in readers’ subsequent experiences—to be persuasive, in the usual human, Bayesian, weight-of-evidence sense.

To me the most essential feature of these episodes is the exploitation of victimhood. Men have a deep instinct to protect women, and some women take advantage of that by claiming to have been harmed or under threat of harm. They do this to gain attention, fame or money, or simply to nullify their shame over something to which they consented but later regretted.

The idea that a trauma has occurred—a trauma that continues to victimize the victim—is arguably the central thread in the history of hysteria. It is evident in the old convent possession hysterias, in female-dominated spirit possession syndromes that still exist in the Third World, and in all the modern-era, medicalized forms of hysteria, going back to Charcot—whose studies of hysterics in the late 1800s are often credited with having kicked off modern psychiatry.

As I see it, another core feature of these phenomena is their ability to grow and spread as a social contagion. Convent hysterias tended to spread infectiously within the walls of individual convents. In some cases, affected young women, sent from one convent to another as part of a dispersal strategy, would seed outbreaks of hysterical behavior in their new institutions. Hysterias in more open settings, such as the one at Salem that began with a group of girls and women acting out “possession” behaviors similar to those seen in European convent episodes, were apt to spread through their communities and into neighboring ones. More modern, medicalized forms of hysteria such as Charcot’s “hysteroepilepsy” of the late 1800s and the “multiple personality disorder” (MPD) that became prominent in the 1980s, also grew in scope as they were publicized and susceptible women learned how to act them out.

Now in the age of the Internet there is the potential for near-instant mass contagions of trauma tales. Even one prominent news story about one alleged victim may be enough to trigger the participation of others from around the world. The Epstein, Weinstein, Kavanagh and Cosby cases all seem to have been driven by this “broadcast” effect.

What about the truth of the claims in these episodes? If a man actually has engaged in serial sexual assault, and his victims complain to the police so that charges are brought against him, how is that “hysteria” or anyway a remarkable social phenomenon requiring explanation? My response is that in such cases there may not be a need for an explanation, but that I’m not referring to such cases here. I’m referring to cases where the claims are obviously to some extent false or exaggerated or opportunistic, tend to be used in ways that go beyond mere law enforcement, occur after delays that may extend for years or decades, and come in cascades that strongly suggest a social contagion. The vast majority of real sexual assault cases, even those involving repeat offenders, never make it past the back pages of the newspapers and don’t generate social phenomena such as I’m describing here.

Another frequent, though not universal, theme in these stories is the victim’s loss of agency—an utter helplessness on her part that implicitly absolves her of any responsibility for her plight, and underscores her urgent need for aid and sympathy. In premodern and early-modern spirit-possession cases the loss of agency was complete by definition and usually was the traumatic event. Late 20th century MPD cases worked in almost but not quite the same way: The victim’s “dissociation” into “alter personalities” was not the trauma itself but, rather, a reaction to the trauma. As one prominent pro-MPD psychiatrist put it at the time, MPD is the victim imagining that the abuse she is suffering is happening to someone else. However, in both spirit-possession and MPD, the possessing spirits and alters serve as impressive behavioral symbols of the victim’s traumatized state, and often, more literally, act as her authoritative spokespersons—her Gloria Allreds, if you like.

Similarly, Charcot’s hysterics of the 1880s, though they were not afflicted by spirits or alters, were seized by mysterious syndromes that mimicked epilepsies or movement disorders and ostensibly robbed them of their will, contorting their bodies and putting them into trance, “hypnotic” states. The theme of hypnosis, of course, runs through virtually all modern forms of hysteria, as a route to the hysterical state of consciousness and the retrieval of buried trauma memories—and as a suspender of ordinary consciousness and agency.

The loss-of-agency theme is less prominent but still present in more modern, matter-of-fact cascades of sex assault claims, where it continues to underscore the victim’s victimhood. In the Cosby case, for example, his accusers typically acknowledged having dined with him, having drunk alcohol with him, having gone to his hotel room at night, or having done other things that hint at some degree of volition. But virtually all of these women claimed or suggested that Cosby had then robbed them of their ability to resist by slipping them tranquilizer or “knock out” pills of one kind or another. Weinstein’s accusers, for their part, have spoken of his coercion and threats, of his menacing bulk, of his power to destroy their careers. Epstein’s accusers have claimed in some cases that he “enslaved” them, if not by actually clapping them in chains then by flying them to remote islands from which no escape was possible. I am not suggesting that any of these men is innocent, but I think it’s worth noting that very few of the victims in these cases have claimed simply, let alone promptly, that they fought back against the accused but were overpowered.

Perps and buried memories

Historically the most prominent cascades of trauma tales, such as the witchcraft mass-hysterias of the late medieval and early modern era, and the MPD-related mass-hysterias of the 1980s-90s, have been those featuring accusations against real people—accusations of witchcraft or Satan-worship or sexual assault, or some combination thereof. That the older, pre-20th-century subset of these cases resulted in the jailings and executions of hundreds or thousands of innocent people in Europe and America is well known. Less well known is that the MPD/Satanic-ritual-abuse (SRA)/recovered-memory scares of very recent decades harmed similar numbers of people across the Western world, through false accusations, wrongful prosecutions, and in many cases wrongful and lengthy jailings. The latter episode also corrupted, and exposed the deep corruptibility of, the social work and psychotherapy-related professions, not to mention the media.

But cascades of trauma tales are not always dependent on claims against human perpetrators. One of the more prominent recovered-memory variants that arose in the 1980s and 90s featured trauma-tales that were every bit as lurid as those of MPD/SRA, and often seemed to have been tailored to grab public attention, but lacked human perpetrators and almost never involved law enforcement. This was the “alien abduction” epidemic. Like some of the older spirit-possession cases, abduction stories replaced human perps with otherworldly ones—aliens in this case, of all shapes and sizes, though usually they were said to be the huge-eyed, bulge-headed “greys” that were already prominent in the UFO lore.

The recovered-memory epidemic in all its major variants burned out by the late 1990s, in part because it made enemies of hundreds of wrongfully charged defendants and their families, and in general clashed with traditional mechanisms of due-process (which had developed partly in reaction to early-modern hysterias). The real tipping point seems to have been the development of a consensus in psychiatry and law-enforcement that many of the claimants were fantasists and hypnosis-recovered memories were mostly or entirely confabulations.

Beyond hypnosis

However, around the time that the recovered-memory craze dissolved, a new and remarkably similar epidemic involving traumatic memories started becoming very common. In this syndrome the patient, usually female, complained of sleeplessness, fibromyalgia, irritable bowels, chronic fatigue, or other selections from the rich lore of psychosomatic illness. Instead of hinting that these symptoms derived from some buried trauma-memory, as in the now-discredited recovered-memory epidemic, the patient attributed them to an accessible trauma-memory, perhaps of a recent car accident or divorce, or even something as common as childbirth. It was an easy route to victimhood and the tangible and intangible benefits that went along with that status. For women—also men—in the military, who had no shortage of alleged “traumas” to choose from, and could use such claims to get taxpayer-funded “disability” benefits, it was almost literally a gold mine.

I am describing PTSD, of course—Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. As a clinical entity it was rare in the 1960s/70s world where I grew up. Now it is easily one of the most common psychiatric diagnoses: even in the early 2000s NIMH estimated that more than 5 percent of women and almost 2 percent of men in the US “had PTSD” in the past year (“past-year prevalence”). In the US military, where a PTSD diagnosis can be a monetary gift that keeps on giving, the prevalence has been much higher—even among men, now that the benefits of victimhood in this context are monetary, i.e., go beyond the psychological comforts of victimhood that tend to draw women almost exclusively.

Despite its alleged roots in World War I and earlier “shell shock” cases, PTSD is essentially a modern, culture-bound syndrome. It first came to prominence as a veterans’ complaint with the help of Vietnam Vet advocacy groups in the aftermath of that war. However, as the recovered-memory epidemic receded in the 1990s, sensitive women and their enablers in the rapidly feminizing medical profession began adopting it as a civilian, primarily female illness. From the perspective of a hysteria-aware skeptic, it was and continues to be almost perfect as a replacement for recovered-memory syndromes. There is no reliance on hypnosis, nor does it require claims against a human perp and resulting scrutiny from the judicial system. In a newly feminized, newly sensitized age, how can it even be questioned? Therapists or psychiatrists who doubt its validity (a validity that is of course enshrined in the latest DSM editions) can lose not only their patients but also their professional reputations, even their licenses to practice. Skepticism from within academia or the medical profession therefore has been rare. And when doubts have been expressed they usually have been expressed in opaque academese.

Nothing that I have written in this book should be construed as trivializing the acts of violence and the terrible personal losses that stand behind many traumatic memories. The suffering is real; PTSD is real. But can one also say that the facts now attached to PTSD are true (timeless) as well as real? Can questions about truth be divorced from the social, cognitive, and technological conditions through which researchers and clinicians come to know their facts and the meaning of facticity…? My answer is no. [in Allan Young’s The Harmony of Illusions]

MeToo: Hysteria Lite

In the paragraphs above I’ve touched on the Weinstein, Epstein, Cosby and Kavanagh cases—classic early 21st century #MeToo stories that ostensibly are free of traditional hysterical themes such as spirit possession, witchcraft and somatization disorders. They involve trauma claims but are not cases for therapists or priests or witch-doctors to handle—they are criminal cases or at least cases involving allegations of serious personal misconduct. Yet they involve seemingly infectious cascades of claims, and my hypothesis here is that they feature essentially the same behavioral program that drives other, more frankly hysterical trauma-story cascades. The claims against a Weinstein or a Cosby may be more veridical than those of a 16th century novice nun who pretends to be possessed by a demon sent by some priest, but they cascade in the same way, and involve at least some degree of exaggeration and falsehood—as should be evident from even a cursory critical analysis of these cases.

Moreover, there seems to be a social aura of intense feeling around these cases. They don’t exist in isolation as civil or criminal matters to be decided by a sober, judicial weighing of facts. Many women are fiercely, often blindly supportive of the plaintiffs, and are ready to punish anyone who is insensitive enough to express skepticism. Some men too have their protective instincts activated and are also strongly supportive. Many of the rest, perhaps a large majority, are skeptical but know better than to draw adverse attention by saying anything. A few, of course, do voice their skepticism and catch hell for it—and though their skepticism may be well founded and perfectly logical, even obvious, we tend to see such people as foolish rather than honest or brave or perspicacious. An unspoken but widely accepted fact about hysterias and related trauma-tale cascades is that the truth has little power against the mass emotions they harness.

A Peculiarly Feminine Power

“Power” may be an essential concept here. One can speculate almost endlessly about this sort of thing, but an obvious hypothesis is that these female-driven trauma-tale cascades are, at least in part, manifestations of an ancient, instinctive “asymmetrical warfare” tactic—a means by which women can defeat men who are on an individual basis physically and psychologically more powerful. As one well known anthropologist, speaking of female-dominated African possession cults, has put it:

zar possession provides women patients (acting consciously or unconsciously) with an opportunity to pursue their interests and demands in a context of male dominance. [I.M. Lewis, Ecstatic Religion, p. 71]

Where they are given little domestic security and are otherwise ill-protected from the pressures and exactions of men, women may thus resort to spirit possession as a means both of airing their grievances obliquely, and of gaining some satisfaction. [Lewis, p. 68]

If women have evolved an instinct to use this tactic, or have evolved traits that otherwise favor that behavioral pattern, it’s at least conceivable that men would have evolved their own way of responding. Curiously, though, the way men respond in modern times and cultures seems to be inefficient at best. The accused tend to try to placate the female complainants or otherwise try to avoid the wrath of the furies that have been whipped up against them, yet usually end up facing the mob alone. There is very little of the male banding-together that could provide an effective defense. Perhaps most bystander men in this situation instinctively sense that they are better off not getting involved. In cases where the woman is alleging that a man has victimized her, a certain proportion of men will be sympathetic and protective to her—thus further hindering any male solidarity.

If women have evolved this cascade tactic as a way of evening up the scales against men, it makes sense that they would use it or adapt it for situations in which (a) they can activate the necessary network of claimants, and (b) they can use it to achieve some goal that would otherwise be harder to reach. Conceivably the modern media-driven cascades aimed at “canceling” or “de-platforming” people who have done or said something politically incorrect owe something to this feminine tradition. The complainants who join these cascades usually point to a broader harm committed by the target person, for example against a minority group whom the target has slighted. But they often use terminology reminiscent of older, trauma-tale cascades, i.e., suggesting that they themselves have been victimized and traumatized. In a recent essay on the notorious Larry Summers cancellation in 2005, I noted the language used by one of the prominent complainants in that case, MIT professor Nancy Hopkins.

“When he started talking about innate differences in aptitude between men and women, I just couldn’t breathe because this kind of bias makes me physically ill,” Dr. Hopkins said.

Cancellations of people who violate political correctness codes are frequently labeled “witch hunts,” but I think the analogy is not as loose as people tend to assume. Witch-hunts, such as the New England variety, were led by a different and more clearly defined “authority” than the relatively amorphous journalist-activist network that presides over modern p.c.-violation cases. But in both situations, we see a central dynamic in which an initial accusation against a target is followed by a contagious piling-on of claims and vilification until—usually—the miscreant issues a groveling apology, loses his job, or suffers some other adverse outcome. And although there are no data on this, it seems obvious to me from ordinary experience that women are vastly overrepresented among the claimants in these cascades.

Cascade control

Is there any effective response to cascades of this nature? I get the sense that this question tends to be asked most urgently these days about cancellation cascades, which are often unambiguously irrational and unjust. In the Larry Summers cancellation of 2005/06, with which I’m relatively familiar, reasoned argument by high-profile defenders of Summers, including the popular writer Steven Pinker, writing in high-profile publications, counted for remarkably little against the emotional storm conjured up by a handful of feminist academics and their media enablers.

That attack on Summers clearly was aimed at causing him professional harm—he was then the president of Harvard College. Professional harm was the outcome too, for that and countless other cancellations in recent years. Shouldn’t the law provide a remedy in such cases?

It should perhaps, but it doesn’t, and arguably that’s a big part of the problem. In the 1600s and 1700s in Britain and America, tort law actually did provide good remedies, and (with some notable exceptions) increasingly good deterrence, against the very serious slander/defamation of calling someone a witch. Hysterias such as the one at Salem also provided salutary examples of the harm that could be caused when such defamations went uncontested. But beliefs in witchcraft abated in the century or so after Salem, and in general tort law has never adapted to the fact that witchcraft accusations can have modern variants that are despiritualized but still have very serious reputational and economic consequences. That problem would be fixed, at least at the level of conservative-leaning states, if legislators could strengthen laws meant to protect against this sort of harm—in a way that could survive the inevitable First-Amendment-based challenge from federal courts.

Another element of an effective response would be a response that is just as organized and networked and vocal and goal-directed as the attack. Victims of cancellation cascades tend to be isolated and overwhelmed in the mediasphere by howling mobs that intimidate not only the victims but also their employers and would-be supporters, until the victim loses his job and status. One of the more remarkable aspects of the Age of P.C. is the degree to which big corporations have been cowed by such mobs. It’s hard to avoid the conclusion that having a louder, more numerous mob on your side—a mob that brings a credible threat of a mass boycott of any company that crosses it—could make all the difference in such cases. Implementing this strategy would mean organizing the Right to oppose almost instinctively any media-driven cascade aimed at canceling someone for a political-correctness violation.

Organizing the Right to this extent seems problematic at present, though. Broadly speaking, the Right lacks the relatively energizing and binding “religiosity” of the modern progressive Left—lacks the Left’s youthfulness too. There is no right-wing equivalent of Antifa. Contemporary corporations seem to sense pretty well that the Left coheres better and thus poses a greater threat to their profits.

On the other hand, considering that hysterias tend to fade out as soon as they are widely seen as such, it might help a lot just to shine a light on this phenomenon—in other words, as I’m trying to do here, by calling attention to cancellation cascades and trauma-tale cascades as putative manifestations of an ancient, hysteria-related behavioral program. To some extent we do this already when we compare cancellation cascades to witch hunts, but we could take it further by arguing that the comparison is more than just metaphorical, and may have ancient roots in female social behavior—behavior that, due to the mass-entry of women into public life in the last half-century, has been more culturally consequential than ever before in history. There must be a reason that feminists, despite their unprecedented grip on Western culture, keep complaining about women’s “powerlessness” with respect to men. Perhaps that illusion of weakness is essential to their actual and ascendant power.

***

Author’s note (Oct 2022):

I’d appreciate it, reader, if you would link to my essays on cultural feminization (or otherwise cite them) wherever you see this topic being discussed. I’ve been writing about “cult-fem” for more than a decade—which, as far as I know, is much longer than anyone else. Some of my essays have circulated widely in recent years, and I’ve even placed one in a moderately well-read webzine. I like to think that my contributions have helped seed what is becoming an important public discourse. Yet those contributions of mine are almost never acknowledged by the better-known opinionators who have ventured into this realm in the last year or so. Being pseudonymous and writing principally from a personal website seem to have left me in the unhappy state of being “much read but seldom cited.” (I discuss the general problem of citation in the Internet age in my short essay “The Tree of Knowledge.”)

Also, though I don’t charge a subscription to this website, or put ads on it, or even solicit donations, you could buy a copy of my e-book (see image below, linked to its Amazon page) if you’d like to support my writing.