A quick summary for those coming to this for the first time.

I’ve been in the habit of citing one of my 2019 essays, “The Great Feminization” or “The Day the Logic Died,” as an introduction to the idea of cultural feminization. Since those pieces were written, though, I’ve posted other essays on this topic, expanding this “idea space” a bit more with each one. So it might be useful now, to those coming to this for the first time, to have an updated short summary of the whole picture as I see it.

In a Nutshell

Women, because of their different ways of thinking and behaving on average, and their new, strong influence over culture and politics, are the principal drivers of modern social change, including all aspects of wokeness.

From Home to Office

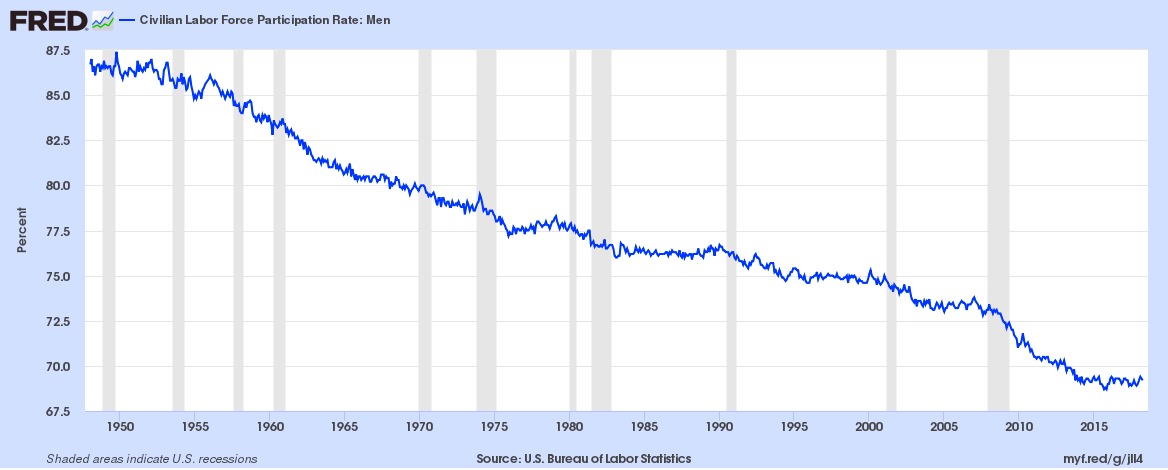

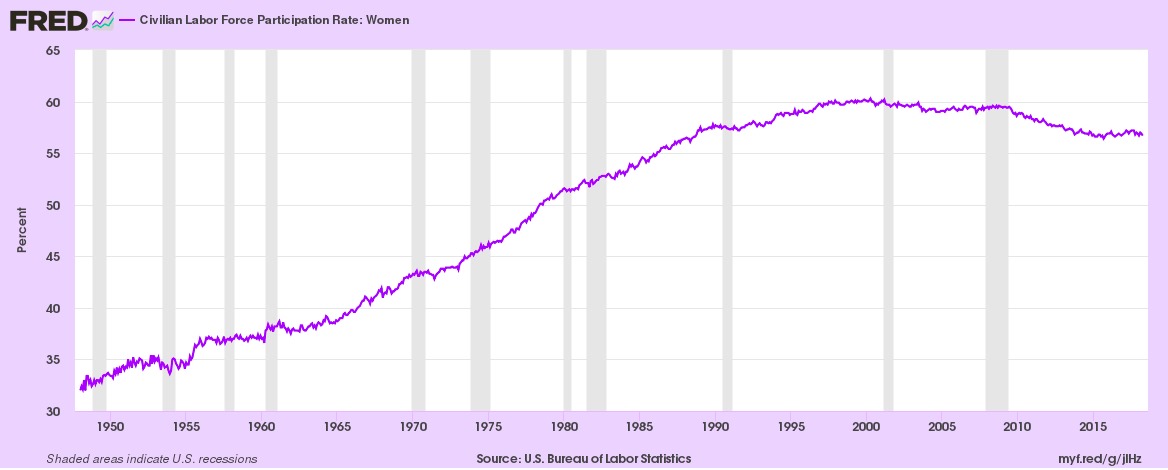

American women—whose sociocultural circumstances are very similar to those of other Western women—obtained full equality in voting rights by constitutional amendment more than a century ago. That had significant cultural and political consequences, but it was only a small part of the story of women’s modern empowerment. The big change occurred in the period 1950-2000, when women shifted, en masse and on a durable, peacetime basis, from being dedicated homemakers to participating more or less equally alongside men in the working world and public life. The labor force participation rate charts below (the first for American men, the second for women) clearly show this shift.

As I wrote in “The Great Feminization”:

The historic significance of this migration on its own appears to have been underappreciated. Women never made such a move, to such a degree, in any large human society in the past. It significantly altered the structure of ordinary life.

But women in the late 20th century didn’t just move into the workforce. They moved into its upper ranks, to professions that strongly influence societal culture and policy. They became journalists, public relations specialists, lawyers, academics, novelists, publishers, filmmakers, TV producers, and politicians, all to an unprecedented extent. In some of these culture-making professions, by the 1990s and early 2000s, they had achieved parity or even dominance (e.g., writers, authors, and public relations specialists) with respect to men. Even where they fell short of full parity, they appeared to acquire considerable “veto” power over content. A 2017 report by the Women’s Media Center noted evidence that at the vast majority of media companies, at least one woman is among the top three editors.

Women Think Differently About Cultural and Political Matters

Women’s ascension to power in culture- and policy-making professions has been followed by extensive cultural and political changes. Why? Because women, on average, think differently than men do about cultural and political issues. This should not be surprising: The bodies and minds of women and men were shaped long ago by biological and cultural evolution for their distinct traditional roles in life. Women’s distinct roles obviously have required certain psychological traits or tendencies that are different from male traits. I think most of us would agree that these innately feminine traits include:

-

- A greater emotional sensitivity and capacity for empathy/compassion/nurturing.

-

- A greater fearfulness and aversion to risks (concerning dangers to themselves and others), including an extra sensitivity to the risks of toxic and other environmental threats (reflected in hormone-driven pregnancy behaviors such as food/odor aversions and compulsive “nesting”).

-

- A greater affinity for people and relationships, and lesser affinity for constructed, systemized, and abstract things.

-

- A greater tendency to align emotionally when in a group, especially a group of other women—a tendency that implies a superior ability (individually and collectively) to transmit emotions and other social contagions.

-

- A reduced affinity for competition and capacity for resistance to aggressors.

-

- Greater affinity for themes of suffering and victimhood, with correspondingly less interest in triumphant “male” themes of exploration and conquest.

Probably most of these traits are interrelated. In any case, when one considers these broad aspects of “innate femininity,” it isn’t hard to see that the very sudden extension of their dominance—from women’s traditional domestic domain to all areas of public life—would help account for the dramatic social changes of the past half-century or so.

It also isn’t hard to see that women tend to support these social changes more than men do—although it’s important to understand that by altering the culture, women have influenced not only their own but also men’s thinking and behavior.

Social changes likely to have been driven by the ascendancy of female traits

-

- Much more generous welfare programs.

-

- Extensions of the concept of welfare to include more types of intervention (e.g., affirmative action) and more groups needing intervention (“traditionally marginalized groups”).

-

- Excessively honoring (e.g., with pronoun declaration rituals) anyone with a claim to victimhood or some other “special identity” status.

-

- Very strong social reactions to media portrayals of racial injustice/inequity, e.g., the near-hysterias following the police killings of Michael Brown in Ferguson, MO and George Floyd in Minneapolis, MN.

-

- Inflations of the traditional definitions of “harm,” “offense,” “trauma,” “violence,” “aggression,” etc., as reflected in new terms such as “microaggressions” and “triggers.”

-

- An astounding belief (from men’s perspective) in slight or even imaginary emotional upsets as sources of real harm in the world. This belief is reflected in everyday female-produced media content but also in the new hyper-focus on psychological trauma in law and medicine, and of course in the vast inflation of trauma-related syndromes such as PTSD (and the recovered-trauma-memory syndromes of the 1980s/90s, before they were discredited).

-

- A shift away from the traditional deterrence of criminal behavior with punishment and stigmatization, in preference for compassion-based, non-stigmatizing solutions (e.g., non-prosecute policies for most crimes, free needles for addicts).

-

- Reduced tolerance of deaths in war, despite (ironically) a greater inclination to enter foreign conflicts in response to emotion-evoking atrocities portrayed on television.

-

- Less tolerance for capital punishment and other harsh sentences, especially where the “traditionally disadvantaged” are concerned.

-

- Less restrictive immigration policy, again driven by stories and imagery (pitiable refugee children, huddled masses, etc.) that evoke maternal protective/nurturing instincts.

-

- In general, much more emphasis in media and policy contexts on compassion-evoking stories of individuals, with correspondingly less emphasis on (even condemnation of!) coldly logical risk/benefit analyses focused on the long term.

-

- Suppression of potentially upsetting ideas or expressions (“hate speech,” “mansplaining”), words, facts (e.g., on racial differences in criminality), free debate and free speech, due process of law (especially when women are plaintiffs), and even some fields of scientific inquiry.

-

- Helicopter parenting.

-

- Obsession with safety, e.g., as seen in new terms such as “safe space.”

-

- Rise of “green” movement and related cultural themes involving opposition to nuclear power, GMO, “toxins,” “chemicals,” even vaccines (a movement that was increasing in popularity, with female leadership, pre-COVID-19). Related shift towards “natural” foods and medicines, including those produced by the relatively unregulated supplements industry. Rise of hysteria variants involving claims of chemical hypersensitivity, toxic metals, etc.

-

- Decline in interest in engineering, as shown by greater reliance on foreign-born students at e-schools, loss of Western pre-eminence (to China) in advanced engineering projects.

-

- Predominance of “social media” in Western life.

-

- Shift away from technical themes and toward social (woke) themes in female-dominated STEM media and professions, e.g., “math is white supremacist.”

-

- Shift away from traditional, hierarchical, rule-based religions toward more loosely structured and therapeutic forms of worship and spirituality.

-

- Frequent and rapid social contagions of new cultural themes (e.g., wokeness and its various associated behaviors and terminology, from BLM worship to the trans mania), affecting virtually all organizations and institutions—because women, the chief transmitters of these contagions, are highly influential in organizations and institutions.

-

- Increase in the frequency and prevalence of overtly pathological social contagions (hysterias) such as Tik-Tok-induced Tourette’s-like behavior.

-

- Tendency of professions and institutions to become female-dominated by systematically excluding (especially white) males—who are “problematic” for grouped women, simply because of their innate male resistance to institutional feminization.

-

- General increase in intolerant, “hive-mind” behavior in institutions and professions as a consequence of increasing female dominance.

-

- Marked preference for inclusivity and equity over traditional meritocratic discrimination, everywhere from schools to companies to political appointees and candidates. “Participation trophies.”

-

- Virtually uniform emphasis on victimhood themes in Western literary fiction, coincident with female takeover of publishing industry.

-

- Reduced public interest in adventurous endeavors such as manned space exploration (“we should fix poverty and inequality here on Earth first”).

-

- Demotion of traditional heroes such as Christopher Columbus and Thomas Jefferson and promotion of their alleged victims, e.g., Native Americans, Sally Hemings.

Obviously, not every woman out there likes or is driving these changes. The differences between men’s and women’s mindsets are differences on average.

Moreover, the mindset underlying these shifts—a mindset that, in some of these cases, seems sensitive to the point of neuroticism—might not even be that of the average woman. I suspect it more closely represents the attitudes of the single, childless activists who have been most energetic in pushing these social changes. For them, perhaps, society and its “disadvantaged,” from African-Americans to Rio Grande-crossing illegal immigrants, are substitutes for the children they don’t have.

Cultural Feminization is Problematic

One sufficient and conservative reason for doubting that cultural feminization is a good thing is simply that it entails the abrupt replacement of a large set of civilizational traits that were embedded in Western people, culturally and probably biologically, over thousands of years. Not every Western trait is essential to the West’s survival or is even still adaptive in the modern world. But discarding these traits at the whim of female activists seems a bit like deleting genes willy-nilly from the human genome. Could you do that without bad consequences? Yes, conceivably—but it’s far more likely to end in disaster.

Another good reason to oppose or limit cultural feminization is that, while men traditionally led societies and thus would have been expected to evolve attitudes and behaviors appropriate for that role, women traditionally were confined to other, more private roles, centering on maternity. In other words, why should we suppose that being a mother, or being shaped by evolution for motherhood, is a better preparation for public life than . . . serving in public life, as men have done for ages?

There are further reasons that have to do with specific effects of feminization. For example, feminization appears to have brought a new cultural and political emphasis on short-term, feelgood consequences, with less emphasis on—I would say a blindness to—long-term consequences. It should be obvious that this is unsustainable and must end badly.

Moreover, females’ lesser affinity, even hostility, for due process of law, free debate, unfettered scientific inquiry, and related aspects of Western, small-l liberalism, seems likely to render the West relatively static, sclerotic, and poor if allowed to run to its logical conclusion.

Then, of course, there is the apparent female (relative to male) embrace of mass immigration to the West from the Third World, which I think has the potential to dissolve Western societies faster than any other factor.

I think it’s worth mentioning too, though it’s more speculative, that the apparent decades-long slide in testosterone levels in men might be an effect of cultural feminization. Testosterone levels in men (and women) are known to be regulated by social cues, such as winning or losing competitions, and so it would make sense that cultural messaging condemning and suppressing traditional masculinity would have a T-lowering effect. Lower T means lower fertility, which below a certain threshold—one that Legacy Americans sank beneath long ago—leads ultimately to the extinction of the population.

Lastly, there is the sense of taboo that enshrouds the idea of cultural feminization, in general but especially when it is framed negatively. The high-profile MSM types (Cowen, Edsall) who have touched the subject (only in the last year or so, as far as I know) have been approving or very mild in their concerns. Also, for more than a decade now, most of the short essays I’ve tried to get published on this subject, including in some pretty right wing publications, have been rejected. In every case, a female editor had veto power, and I think her male colleagues also feared the hostile ululations that would ensue if they published my unvarnished take. Anyhow, an old quote (often attributed to Voltaire) seems apt here: “If you want to know who rules over you, look at whom you’re not allowed to criticize.”

Further reading

“The Great Feminization” (2019)

“The Day the Logic Died” (2019)

“Cultural Feminization: a Bibliography” (2021)

The Great Feminization: Women as Drivers of Modern Social Change (2022)

* * *

Author’s note:

I’d appreciate it, reader, if you would link to my essays on cultural feminization (or otherwise cite them) wherever you see this topic being discussed. I’ve been writing about “cult-fem” for more than a decade—which, as far as I know, is much longer than anyone else. Some of my essays have circulated widely in recent years, and I’ve even placed one in a moderately well-read webzine. I like to think that my contributions have helped seed what is becoming an important public discourse. Yet those contributions of mine are almost never acknowledged by the better-known opinionators who have ventured into this realm in the last year or so. Being pseudonymous and writing principally from a personal website seem to have left me in the unhappy state of being “much read but seldom cited.” (I discuss the general problem of citation in the Internet age in my short essay “The Tree of Knowledge.”)

Also, though I don’t charge a subscription to this website, or put ads on it, or even solicit donations, you could buy a copy of my e-book (see image below, linked to its Amazon page) if you’d like to support my writing.